Bumi datar

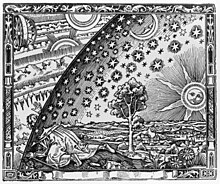

Model Bumi datar adalah sebuah konsepsi arkais dari bentuk Bumi sebagai bidang atau cakram. Banyak dari kebudayaan kuno menganut kosmografi bumi datar, yang meliputi Yunani sampai jaman klasik, sipilisasi Zaman Perunggu dan Zaman Besi dari Timur Dekat sampai periode Hellenistik, India sampai zaman Gupta (awal abad-abad Masehi), dan Tiongkok sampai abad ke-17. Paradigma tersebut juga biasanya dipegang dalam budaya-budaya orang asli benua Amerika, dan pernyataan bahwa Bumi datar dikubahi oleh cakrawala dalam bentuk mangkuk adalah hal umum dalam masyarakat pra-saintifik.[1]

Gagasan Bumi bulat dikemukakan oleh seorang filsuf Yunani yaitu Pythagoras[2][3] (abad ke-6 SM), meskipun kebanyakan masyarakat pra-Sokratik (abad ke 6 – 5 SM) meyakini model Bumi datar. Aristoteles memberikan bukti bentuk bulat Bumi pada sekitar 330 SM. Pengetahuan Bumi bulat secara bertahan mulai menyebar pada dunia Hellenistik sejak saat itu.[4][5][6][7]

Teori-teori Bumi datar modern, seperti hal-hal yang diutarakan oleh perhimpunan Bumi datar modern, umumnya dicap pseudosains.[8]

Referensi

- ^ "Their cosmography as far as we know anything about it was practically of one type up til the time of the white man's arrival upon the scene. That of the Borneo Dayaks may furnish us with some idea of it. 'They consider the Earth to be a flat surface, whilst the heavens are a dome, a kind of glass shade which covers the Earth and comes in contact with it at the horizon.'" Lucien Levy-Bruhl, Primitive Mentality (repr. Boston: Beacon, 1966) 353; "The usual primitive conception of the world's form ... [is] flat and round below and surmounted above by a solid firmament in the shape of an inverted bowl." H. B. Alexander, The Mythology of All Races 10: North American (repr. New York: Cooper Square, 1964) 249.

- ^ Dicks, D.R. (1970). Early Greek Astronomy to Aristotle. hlm. 72–198. ISBN 9780801405617.

- ^ Walter Burkert, (1 June 1972), Lore and Science in Ancient Pythagoreanism, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-53918-1, 1972, hlm. 306.

- ^ Continuation of Greek concept into Roman and medieval Christian thought: Reinhard Krüger: Materialien und Dokumente zur mittelalterlichen Erdkugeltheorie von der Spätantike bis zur Kolumbusfahrt (1492)

- ^ Direct adoption of the Greek concept by Islam: Ragep, F. Jamil: "Astronomy", in: Krämer, Gudrun (ed.) et al.: Encyclopaedia of Islam, THREE, Brill 2010, without page numbers

- ^ Direct adoption by India: D. Pingree: "History of Mathematical Astronomy in India", Dictionary of Scientific Biography, Vol. 15 (1978), pp. 533−633 (554f.); Glick, Thomas F., Livesey, Steven John, Wallis, Faith (eds.): "Medieval Science, Technology, and Medicine: An Encyclopedia", Routledge, New York 2005, ISBN 0-415-96930-1, p. 463

- ^ Adoption by China via European science: Jean-Claude Martzloff, "Space and Time in Chinese Texts of Astronomy and of Mathematical Astronomy in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries", Chinese Science 11 (1993-94): 66-92 (69) and Christopher Cullen, "A Chinese Eratosthenes of the Flat Earth: A Study of a Fragment of Cosmology in Huai Nan tzu 淮 南 子", Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, Vol. 39, No. 1 (1976), pp. 106-127 (107)

- ^ MacDougall, Robert. "Strange enthusiasms: a brief history of American pseudoscience". Columbia University. Diakses tanggal July 5, 2016.

Bacaan tambahan

- Fraser, Raymond (2007). When The Earth Was Flat: Remembering Leonard Cohen, Alden Nowlan, the Flat Earth Society, the King James monarchy hoax, the Montreal Story Tellers and other curious matters. Black Moss Press, ISBN 978-0-88753-439-3

- Garwood, Christine (2007) Flat Earth: The History of an Infamous Idea, Pan Books, ISBN 1-4050-4702-X

- Simek, Rudolf (1996). Heaven and Earth in the Middle Ages: The Physical World Before Columbus. Angela Hall (trans.). The Boydell Press. Diakses tanggal February 9, 2013.

Pranala luar

- (Inggris) The Myth of the Flat Earth

- (Inggris) The Myth of the Flat Universe

- (Inggris) You say the earth is round? Prove it (from The Straight Dope)

- (Inggris) Flat Earth Fallacy

- (Inggris) Zetetic Astronomy, or Earth Not a Globe by Parallax (Samuel Birley Rowbotham (1816-1884)) at sacred-texts.com

- (Inggris) The flat-earth myth and creationism

- (Inggris) The Flat Earth Society official website

- (Indonesia) Flat Earth 101 - Flat Earth Indonesia