Shitao

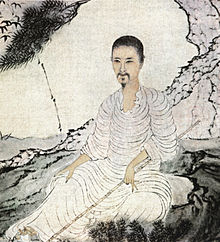

Shi Tao (Hanzi sederhana: 石涛; Hanzi tradisional: 石濤; Pinyin: Shí Tāo; Wade–Giles: Shih T'ao); (1642–1718), terlahir sebagai Zhu Ruoji (朱若極) ialah seorang pelukis lanskap dan penyair Cina pada permulaan zaman Dinasti Qing (1644–1911).[1]

Dilahirkan di Kabupaten Quanzhou di Provinsi Guangxi, Shi Tao ialah anggota istana kerajaan Dinasti Ming. Dia nyaris terkena bencana pada tahun 1644 ketika Dinasti Ming jatuh akibat serangan Manchuria dan pemberontakan sipil. Setelah berhasil menyelamatkan diri, Shi Tao mengambil nama Yuanji Shi Tao sebelum tahun 1651 ketika dia menjadi seorang rahib Buddha.

Dia pindah dari Wuchang, Hubei ketika dia memulai pengajaran keagamaannya, ke Anhui pada dasawarsa 1660-an. Pada dasawarsa 1680-an dia menetap di Nanjing dan Yangzhou, dan pada tahun 1690 dia pindah ke Beijing untuk menjumpai pembimbingnya demi promosinya dalam sistem biara. Kecewa karena gagal menjumpai pembimbing, Shi Tao mengganti keyakinannya menjadi Taoisme pada tahun 1693 dan kembali ke Yangzhou di mana dia menghabiskan sisa hidupnya sampai tahun 1707.

Nama

Shi Tao memiliki lebih daripada 24 nama alias selama hidupnya.[2]

Nama yang paling lazim di antara nama-nama yang digunakan adalah Shi Tao (Gelombang Batu - 石涛), Ku Gua Heshang (Rahib Labu Pahit -苦瓜和尚), Yuan Ji (Penghulu Keselamatan - 原濟), Xia Zun Zhe (Sang Buta Yang Terhormat - 瞎尊者, buta terhadap hasrat duniawi), Da Dizi (Sang Suci (atau terbersihkan) - 大滌子).

Sebagai mantan Buddhis, dia juga dikenal dengan nama kerahiban Yuan Ji (原濟)[3]

Nama Da Dizi digunakan ketika Shitao meninggalkan ajaran Buddha dan memeluk Taoisme. Itu juga menjadi nama yang digunakan untuk rumahnya di (Da Di Hall - 大滌堂).

Seni

Shi Tao adalah salah seorang pelukis individualis paling terkenaldari permulaan zaman Dinasti Qing. Seni yang dia ciptakan dapat dikatakan revolusioner, karena perbedaannya dari teknik dan gaya yang telah baku dan kaku yang sebelumnya dianggap indah. Peniruan dihargai melebihi terobosan, dan meskipun Shi Tao jelas-jelas dipengaruhi oleh para pendahulunya (Ni Zan dan Li Yong), seni yang dia ciptakan menyelisihi cara-cara mereka dalam beberapa cara baru dan memesonakan.

His formal innovations in depiction include drawing attention to the act of painting itself through his use of washes and bold, impressionistic brushstrokes, as well as an interest in subjective perspective and the use of negative or white space to suggest distance. Shi Tao's stylistic innovations are difficult to place in the context of the period. In a colophon dated 1686, Shi Tao wrote: "In painting, there are the Southern and the Northern schools, and in calligraphy, the methods of the Two Wangs (Wang Xizhi and his son Wang Xianzhi). Zhang Rong (443–497) once remarked, 'I regret not that I do not share the Two Wangs' methods, but that the Two Wangs did not share my methods.' If someone asks whether I [Shi Tao] follow the Southern or the Northern School, or whether either school follows me, I hold my belly laughing and reply, 'I always use my own method!'"[4][note 1]

The poetry and calligraphy that accompany his landscapes are just as beautiful, irreverent, and vivid as the paintings they complement. His paintings exemplify the internal contradictions and tensions of the literati or scholar-amateur artist, and they have been interpreted as an invective against art-historical canonization.

"10,000 Ugly Inkblots" is a perfect example of Shi Tao's subversive and ironic aesthetic principles. This uniquely apperceptive work challenges accepted standards of beauty. As the carefully painted landscape degenerates into Pollock-esque splatters, the viewer is forced to recognize that the painting is not transparent (immediate, in the most literal sense meaning without media) in the way it initially purports to be. Solely because they are labeled "ugly," the ink dots begin to take on a sort of abstract beauty.

"Reminiscences of Qin-Huai" is another of Shi Tao's unique paintings. Like many of the paintings from the late Ming Dynasty and early Qing Dynasty it deals with man's place in nature. Upon a first viewing, however, the craggy peak in this painting seems somewhat distorted. What makes this painting so unique is that it appears to depict the mountain bowing. A monk stands placidly on a boat that floats along the Qin-Huai river, staring up in admiration at the genuflecting stone giant. The economy of respect that circulates between man and nature is explored here in a sophisticated style reminiscent of surrealism or magical realism, and bordering on the absurd. Shi Tao himself had visited the river and the surrounding region in the 1680s, but it is unknown whether the album that contains this painting depicts specific places. Re-presentation itself is the only way the feeling of mutual respect that Shi Tao depicts in this painting could be communicated; the subject of a personified mountain simply defies anything simpler.

Catatan

- ^ Paraphrased. The colophon was added to a 1667 hanging scroll of Huang Shan.

Catatan kaki

- ^ Hay 2001, hlm. 1, 84

- ^ Coleman 1978, hlm. 127

- ^ China: five thousand years of history and civilization. Hong Kong: City University of Hong Kong Press. 2007. hlm. 761. ISBN 978-962-037-140-1 Periksa nilai: checksum

|isbn=(bantuan). - ^ Hay 2001, hlm. 243, 250

Referensi

- Hay, Jonathan (2001). Shitao: Painting and Modernity in Early Qing China. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521393426, 9780521393423 Periksa nilai: invalid character

|isbn=(bantuan). - Coleman, Jonathan (1978). Philosophy of Painting by Shih-T'Ao: A Translation and Exposition of His Hua-P'u (Treatise on the Philosophy of Painting) (Studies in Philosophy). The Hague (Noordeinde 41): de Gruyter Mouton. ISBN 9027977569, 978-9027977564 Periksa nilai: invalid character

|isbn=(bantuan).

Pranala luar

- Shi Tao at China Online Museum

- Painting Gallery of Shi Tao at China Online Museum

- Several Paintings

- Works