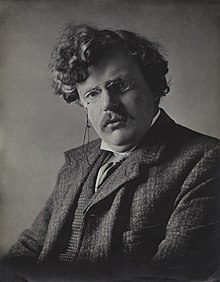

G.K. Chesterton

Gilbert Keith Chesterton, KC*SG (29 Mei 1874 – 14 Juni 1936), lebih dikenal sebagai G. K. Chesterton, adalah seorang penulis Inggris,[2] penyair, filsuf, dramawan, jurnalis, orator, teolog awam, penulis biografi, serta kritikus literer dan seni. Chesterton sering disebut sebagai "pangeran paradoks".[3] Majalah Time mengomentari gaya tulisannya: "Kapan saja memungkinkan Chesterton memberikan pokok-pokok pemikirannya dengan ungkapan populer, pepatah, alegori—pertama-tama dengan benar-benar membalikkannya secara hati-hati."[4]

G. K. Chesterton | |

|---|---|

G. K. Chesterton, foto dari E. H. Mills, 1909. | |

| Lahir | Gilbert Keith Chesterton 29 Mei 1874 Kensington, London, Inggris |

| Meninggal | 14 Juni 1936 (umur 62) Beaconsfield, Buckinghamshire, Inggris |

| Makam | Pemakaman Katolik Roma, Beaconsfield |

| Pekerjaan | Jurnalis, novelis, esais |

| Bahasa | Inggris |

| Kewarganegaraan | Inggris |

| Pendidikan | St Paul's School (London) |

| Almamater | Slade School of Art |

| Periode | 1900–1936 |

| Genre | Esai, Fantasi, apologetika Kristen, apologetika Katolik, Misteri, Puisi |

| Aliran sastra | Kebangunan literer Katolik[1] |

| Karya terkenal | The Napoleon of Notting Hill (1904), Charles Dickens: A Critical Study (1906), The Man Who Was Thursday (1908), Orthodoxy (1908), cerita-cerita Father Brown (1910–1935), The Everlasting Man (1925) |

| Pasangan | Frances Blogg |

| Kerabat | Cecil Chesterton (saudara) |

| Tanda tangan |  |

Chesterton utamanya dikenal karena karya fiksinya tentang seorang detektif-pastor, Father Brown,[5] dan karya-karya apologetikanya yang meyakinkan. Beberapa di antara mereka yang tidak sependapat dengan dia mengakui adanya daya tarik besar dari karya-karya apologetik seperti Orthodoxy dan The Everlasting Man.[4][6] Chesterton sering menyebut dirinya sebagai seorang Kristen "ortodoks", kemudian mengidentifikasi posisinya ini dengan semakin mendekati Katolisisme, dan pada akhirnya beralih dari Gereja Tinggi Anglikanisme ke Gereja Katolik. George Bernard Shaw, "musuh yang bersahabat" dari Chesterton menurut Time, mengatakan tentangnya, "Dia adalah seorang pria genius kolosal [sic]."[4] Para penulis biografi mengidentifikasi Chesterton sebagai salah seorang penerus dari penulis-penulis era Victoria seperti Matthew Arnold, Thomas Carlyle, Kardinal John Henry Newman, dan John Ruskin.[7]

Kehidupan awal

Chesterton lahir di Campden Hill di Kensington, London, putra dari Marie Louise, née Grosjean, dan Edward Chesterton.[8][9] Ia dibaptis pada usia satu bulan dalam Gereja Inggris,[10] kendati keluarganya sendiri terkadang mempraktikkan Unitarianisme.[11] Menurut autobiografinya, saat masih muda Chesterton tertarik dengan okultisme dan, bersama Cecil saudaranya, pernah bereksperimen dengan papan Ouija.[12]

Chesterton menempuh pendidikan di St Paul's School, kemudian masuk Slade School of Art untuk menjadi seorang ilustrator. Slade adalah salah satu departemen University College London, tempat Chesterton mengambil bidang literatur juga, namun ia tidak meraih satu gelar pun dalam kedua bidang tersebut.

Kehidupan keluarga

Chesterton menikahi Frances Blogg pada 1901; perkawinan tersebut berlangsung seumur hidup mereka. Chesterton memandang Frances berjasa membawanya kembali ke Anglikanisme, meski di kemudian hari ia memandang Anglikanisme sebagai suatu "pale imitation" ("tiruan yang tidak mengesankan"). Chesterton memasuki persekutuan penuh dengan Gereja Katolik pada tahun 1922,[13] dan sang istri mengikuti jejaknya empat tahun kemudian.[14]

Karier

Pada bulan September 1895, Chesterton mulai bekerja untuk salah satu penerbit London, Redway, bertahan di sana lebih dari satu tahun.[15] Pada bulan Oktober 1896 ia pindah ke penerbit T. Fisher Unwin,[16] bertahan di sana sampai tahun 1902. Selama periode tersebut ia juga mengerjakan karya jurnalistik pertamanya, sebagai seorang kritikus lepas dalam bidang literer dan seni. Pada tahun 1902, Daily News memberinya satu kolom opini mingguan, disusul pada tahun 1905 dengan satu kolom mingguan di The Illustrated London News, yang tetap ia tulis selama tiga puluh tahun berikutnya.

Sejak awal Chesterton menunjukkan talenta dan ketertarikan besar dalam seni. Ia pernah merencanakan untuk menjadi seorang artis, dan tulisannya memperlihatkan suatu visi yang membalut gagasan-gagasan abstrak dalam penggambaran-penggambaran yang konkret dan berkesan. Karya fiksinya bahkan berisi perumpamaan-perumpamaan yang tersembunyikan dengan cermat. Father Brown (Pastor Brown) terus-menerus mengoreksi visi yang salah dari orang-orang yang limbung di tempat terjadinya kejahatan dan pada akhirnya berkelana dengan si pelaku untuk menjalankan peran imamatnya dalam pengakuan dan pertobatan. Sebagai contoh, dalam cerita "The Flying Stars", Pastor Brown meminta karakter Flambeau untuk melepaskan diri dari hidupnya dalam kejahatan: "Masih ada masa muda dan kehormatan serta humor di dalam dirimu; jangan berkhayal bahwa semua barang tersebut akan langgeng dalam kehidupan semacam itu. Orang-orang dapat mempertahankan semacam tingkatan kebaikan, tetapi tidak ada orang yang pernah dapat bertahan pada satu tingkatan kejahatan. Jalan tersebut terus menurun. Orang yang baik menjadi peminum dan berubah jadi kejam; orang yang jujur membunuh dan berdusta tentang hal itu. Banyak orang yang saya kenal mengawalinya seperti Anda menjadi seorang penjahat yang jujur, seorang perampok kaum kaya yang ceria, dan berakhir dengan dicap sebagai kotoran."[17]

Chesterton senang berdebat, sering terlibat dalam perdebatan publik yang bersahabat dengan orang-orang seperti George Bernard Shaw,[18] H. G. Wells, Bertrand Russell, dan Clarence Darrow.[19][20] Menurut autobiografinya, ia dan Shaw sama-sama berperan sebagai koboi dalam suatu film bisu yang tidak pernah dirilis.[21]

Kejenakaan visual

Chesterton berperawakan besar, tingginya 6 kaki 4 inci (1,93 m) dan beratnya sekitar 20 stone 6 pon (130 kg; 286 pon). Lingkar pinggangnya yang besar memunculkan suatu anekdot yang terkenal. Pada saat berlangsungnya Perang Dunia I, seorang wanita di London bertanya mengapa ia tidak "berada di Garis Depan"; ia menjawab, "Jika Anda pergi ke samping, Anda akan melihat kalau saya sedang [di depan]."[22] Pada kesempatan lain ia memberi tahu George Bernard Shaw temannya, "Jika melihat Anda, siapa saja akan mengira kelaparan telah melanda Inggris." Shaw balas menjawab, "Jika melihat Anda, siapa saja akan mengira Anda yang telah menyebabkannya."[23] P. G. Wodehouse pernah mendeskripsikan suatu kecelakaan yang sangat keras suaranya sebagai "suara seperti G. K. Chesterton jatuh ke selembar timah".[24]

Chesterton biasanya mengenakan semacam jubah tanpa lengan dan topi kusut, dengan pedang tongkat di tangan, dan cerutu tergantung di mulutnya. Ia memiliki kecenderungan lupa ke mana ia akan pergi dan melewatkan kereta yang akan membawanya ke tujuan. Dilaporkan bahwa pada beberapa kesempatan ia mengirim telegram kepada Frances istrinya dari tempat yang jauh (dan tidak tepat), dengan tulisan seperti "Saya di Market Harborough. Di mana saya seharusnya?", yang akan dibalas sang istri, "Rumah".[25] (Chesterton sendiri menceritakan kisah tersebut, namun tidak menuliskan dugaan balasan dari istrinya, dalam bab XVI dari autobiografinya.)

Radio

Pada tahun 1931, BBC mengundang Chesterton untuk memberikan serangkaian pembicaraan radio. Ia menerimanya, awalnya hanya untuk sementara. Namun, dari tahun 1932 sampai wafatnya, Chesterton menyampaikan lebih dari 40 sesi pembicaraan setiap tahunnya. Ia diperbolehkan, dan didorong, untuk melakukan improvisasi pada naskah-naskahnya. Hal ini memungkinkan dia untuk mempertahankan suatu karakter yang personal dalam sesi-sesi pembicaraannya, sebagaimana juga keputusan Chesterton untuk memperbolehkan istri dan sekretarisnya untuk duduk bersamanya selama siaran berlangsung.[26]

Sesi-sesi pembicaraan tersebut sangat populer. Setelah Chesterton wafat, salah seorang pejabat BBC berkomentar bahwa, "Dalam satu atau beberapa tahun ke depan, ia sudah akan menjadi suara yang mendominasi dari Broadcasting House."[27]

Wafat dan penghormatan

Chesterton meninggal dunia karena gagal jantung kongestif pada pagi hari tanggal 14 Juni 1936, di rumahnya di Beaconsfield, Buckinghamshire. Kata-kata terakhirnya yang diketahui adalah suatu sapaan yang diungkapkan kepada istrinya. Homili saat Misa Requiem Chesterton di Katedral Westminster, London, disampaikan oleh Ronald Knox, seorang mantan pastor Anglikan, pada tanggal 27 Juni 1936. Knox mengatakan, "Semua orang dari generasi ini telah tumbuh di bawah pengaruh Chesterton dengan sedemikian menyeluruh sehingga kita bahkan tidak tahu kapan kita sedang memikirkan Chesterton."[28] Ia dimakamkan di Pemakaman Katolik di Beaconsfield. Wasiat Chesterton dinilai sebesar £28.389, kira-kira setara dengan £1,3 juta pada tahun 2012.[29]

Menjelang akhir hidup Chesterton di dunia ini, Paus Pius XI menganugerahkannya Komandan Kesatria dengan Bintang dari Orde St. Gregorius Agung (KC*SG).[30] Perhimpunan Chesterton telah mengusulkan agar dia dibeatifikasi.[31] Ia dikenang secara liturgis setiap tanggal 13 Juni oleh Gereja Episkopal di Amerika Serikat, dengan suatu pesta peringatan provisional sebagaimana ditetapkan dalam Konvensi Umum tahun 2009.[32]

Karya tulis

Chesterton menulis sekitar 80 buku, beberapa ratus puisi, sekitar 200 cerita pendek, 4.000 esai, dan sejumlah drama. Ia adalah seorang kritikus sosial dan literer, sejarawan, dramawan, novelis, apolog dan teolog[33][34] Katolik, pendebat, serta penulis cerita misteri. Ia adalah kolumnis Daily News, The Illustrated London News, dan G. K.'s Weekly, yang adalah makalah karyanya sendiri; ia juga menulis artikel-artikel untuk Encyclopædia Britannica, termasuk entri tentang Charles Dickens dan bagian dari entri tentang Humor dalam edisi ke-14 (1929). Karakter rekaannya yang paling terkenal yaitu Father Brown (Pastor Brown), seorang detektif-pastor,[5] yang hanya muncul dalam cerpen-cerpen karyanya, sementara The Man Who Was Thursday dapat dikatakan sebagai novelnya yang paling terkenal. Ia adalah seorang Kristen yang kukuh jauh sebelum ia diterima dalam Gereja Katolik; simbolisme dan tema-tema Kristen terlihat dalam banyak tulisannya. Di Amerika Serikat, tulisan-tulisannya tentang distributisme dipopulerkan melalui The American Review, yang diterbitkan oleh Seward Collins di New York.

Di antara karya-karya nonfiksi yang dihasilkannya, Charles Dickens: A Critical Study (1906) mendapat sejumlah pujian secara umum. Menurut Ian Ker (The Catholic Revival in English Literature, 1845–1961, 2003), "Di mata Chesterton, Dickens termasuk Inggris Merry, bukan Puritan"; Ker menganggap pemikiran Chesterton di Bab IV buku tersebut utamanya timbul dari apresiasi sejati pada Dickens, suatu atribut yang relatif usang dalam pandangan opini-opini literer lainnya pada saat itu.

Karya-karya tulis Chesterton secara konsisten menampilkan kejenakaan dan selera humor. Ia menggunakan paradoks ketika membuat komentar-komentar serius tentang dunia ini, pemerintahan, politik, ekonomi, filsafat, teologi, dan banyak topik lainnya.[35][36]

Karya utama

| Sumber pustaka mengenai G.K. Chesterton |

| By G.K. Chesterton |

|---|

- Chesterton, Gilbert Keith (1904), Ward, M, ed., The Napoleon of Notting Hill, UK: DMU.

- ——— (1905), Heretics, Project Gutenberg, ISBN 978-0-7661-7476-4.

- ——— (1906), Charles Dickens: A Critical Study.

- ——— (1908a), The Man Who Was Thursday.

- ——— (1908b), Orthodoxy.

- ——— (6 July 2008) [1911a], The Innocence of Father Brown, Project Gutenberg's.

- ——— (1911b), Ward, M, ed., The Ballad of the White Horse, UK: DMU.

- ——— (1912), Manalive.

- ———, Father Brown (short stories) (detective fiction).

- ——— (1920), Ward, M, ed., The New Jerusalem, UK: DMU.

- ——— (1922), Eugenics and Other Evils.

- ——— (1923), Saint Francis of Assisi.

- ——— (1925), The Everlasting Man.

- ——— (1933), Saint Thomas Aquinas.

- ——— (1936), The Autobiography.

- ——— (1950), Ward, M, ed., The Common Man, UK: DMU.

Artikel

|

|

|

Cerita pendek

- "The Crime of the Communist," Collier's Weekly, July 1934.

- "The Three Horsemen," Collier's Weekly, April 1935.

- "The Ring of the Lovers," Collier's Weekly, April 1935.

- "A Tall Story," Collier's Weekly, April 1935.

- "The Angry Street – A Bad Dream," Famous Fantastic Mysteries, February 1947.

Serba-serbi

- Elsie M. Lang, Literary London, with an introduction by G. K. Chesterton. London: T. Werner Laurie, 1906.

- George Haw, From Workhouse to Westminster, with an introduction by G.K. Chesterton. London: Cassell & Company, 1907.

- Darrell Figgs, A Vision of Life with an introduction by G.K. Chesterton. London: John Lane, The Bodley Head, 1909.

- C. Creighton Mandell, Hilaire Belloc: The Man and his Work, with an introduction by G. K. Chesterton. London: Methuen & Co., 1916.

- Harendranath Maitra, Hinduism: The World-Ideal, with an introduction by G. K. Chesterton. London: Cecil Palmer & Hayward, 1916.

- Maxim Gorki, Creatures that Once Were Men, with an introduction by G. K. Chesterton. New York: The Modern Library, 1918.

- Sibyl Bristowe, Provocations, with an introduction by G.K. Chesterton. London: Erskine Macdonald, 1918.

- W.J. Lockington, The Soul of Ireland, with an introduction by G.K. Chesterton. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1920.

- Arthur J. Penty, Post-Industrialism, with a preface by G. K. Chesterton. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1922.

- Leonard Merrick, The House of Lynch, with an introduction by G.K. Chesterton. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1923.

- Henri Massis, Defence of the West, with a preface by G. K. Chesterton. London: Harcourt, Brace & Co., 1928.

- Francis Thompson, The Hound of Heaven and other Poems, with an introduction by G.K. Chesterton. Boston: International Pocket Library, 1936.

Catatan

- ^ (Inggris) Ian Ker, The Catholic Revival in English Literature (1845–1961): Newman, Hopkins, Belloc, Chesterton, Greene, Waugh (University of Notre Dame Press, 2003).

- ^ (Inggris) "Obituary", Variety, 17 June 1936

- ^ (Inggris) Douglas, J. D. (24 May 1974). "G.K. Chesterton, the Eccentric Prince of Paradox". Christianity Today. Diakses tanggal 8 July 2014.

- ^ a b c (Inggris) "Orthodoxologist", Time, 11 October 1943, diakses tanggal 24 October 2008.

- ^ a b (Inggris) O'Connor, John. Father Brown on Chesterton, Frederick Muller Ltd., 1937.

- ^ Douglas 1974: "Like his friend Ronald Knox he was both entertainer and Christian apologist. The world never fails to appreciate the combination when it is well done; even evangelicals sometimes give the impression of bestowing a waiver on deviations if a man is enough of a genius."

- ^ (Inggris) Ker, Ian (2011). G. K, Chesterton: A Biography. Oxford University Press, p. 485.

- ^ (Inggris) John Simkin. "G. K. Chesterton". Spartacus Educational.

- ^ (Inggris) Haushalter, Walter M. (1912). "Gilbert Keith Chesterton," The University Magazine, Vol. XI, p. 236.

- ^ Ker (2011), p. 1.

- ^ Ker (2011), p. 13.

- ^ Chesterton 1936, Chapter IV.

- ^ (Inggris) "GK Chesterton's Conversion Story", Socrates 58 (World Wide Web log), Google, March 2007.

- ^ (Inggris) "Requiescant" Diarsipkan 2015-10-10 di Wayback Machine., The Tablet, 17 Dec. 1938. Accessed 11 November 2015.

- ^ Ker (2011), p.41

- ^ Ker (2011), p.41

- ^ (Inggris) Chesterton, G. K. (1911). "The Flying Stars." In: The Innocence of Father Brown. London: Cassell & Company, Ltd., p. 118.

- ^ (Inggris) Do We agree? A Debate between G. K. Chesterton and Bernard Shaw, with Hilaire Belloc in the Chair. London: C. Palmer, 1928.

- ^ (Inggris) "Clarence Darrow debate". American Chesterton Society. Diakses tanggal 21 May 2014.

- ^ (Inggris) "G.K. Chesterton January, 1915". Clarence Darrow digital collection. University of Minnesota Law School. Diarsipkan dari versi asli tanggal 2014-05-21. Diakses tanggal 21 May 2014.

- ^ (Inggris) Autobiography. London: Hutchinson & Co., Ltd., 1936, pp. 231–235.

- ^ (Inggris) Wilson, A. N. (1984). Hilaire Belloc. London: Hamish Hamilton, p. 219.

- ^ (Inggris) Cornelius, Judson K. Literary Humour. Mumbai: St Paul's Books. hlm. 144. ISBN 81-7108-374-9.

- ^ (Inggris) Wodehouse, P.G. (1972), The World of Mr. Mulliner, Barrie and Jenkins, p. 172.

- ^ Ward 1944, chapter XV.

- ^ Ker (2011).

- ^ (Inggris) "G.K. Chesterton - CatholicAuthors.com". catholicauthors.com.

- ^ (Inggris) Lauer, Quentin (1991). G.K. Chesterton: Philosopher Without Portfolio. New York City, NY: Fordham University Press, p. 25.

- ^ (Inggris) Barker, Dudley (1973). G. K. Chesterton: A Biography. New York: Stein and Day, p. 287.

- ^ (Inggris) "Gilbert Keith Chesterton (1874–1936)", Catholic authors.

- ^ (Inggris) Antonio, Gaspari (14 July 2009). ""Blessed" G. K. Chesterton?: Interview on Possible Beatification of English Author". Zenit: The World Seen From Rome. Rome: Innovative Media. Diarsipkan dari versi asli tanggal 2010-06-15. Diakses tanggal 18 October 2010.

- ^ (Inggris) "G. K. Chesterton". satucket.com.

- ^ (Inggris) Bridges, Horace J. (1914). "G. K. Chesterton as Theologian." In: Ethical Addresses. Philadelphia: The American Ethical Union, pp. 21–44.

- ^ (Inggris) Caldecott, Stratford (1999). "Was G.K. Chesterton a Theologian?," The Chesterton Review. (Rep. by CERC: Catholic Education Research Center.)

- ^ (Inggris) Douglas, J. D. "G.K. Chesterton, the Eccentric Prince of Paradox," Christianity Today, 8 January 2001.

- ^ (Inggris) Gray, Robert. "Paradox Was His Doxy," The American Conservative, 23 March 2009.

Bacaan tambahan

- Ahlquist, Dale (2012), The Complete Thinker: The Marvelous Mind of G.K. Chesterton, Ignatius Press, ISBN 978-1-58617-675-4.

- ——— (2003), G.K. Chesterton: Apostle of Common Sense, Ignatius Press, ISBN 978-0-89870-857-8.

- Belmonte, Kevin (2011). Defiant Joy: The Remarkable Life and Impact of G.K. Chesterton. Nashville, Tenn.: Thomas Nelson.

- Blackstock, Alan R. (2012). The Rhetoric of Redemption: Chesterton, Ethical Criticism, and the Common Man. New York. Peter Lang Publishing.

- Braybrooke, Patrick (1922). Gilbert Keith Chesterton. London: Chelsea Publishing Company.

- Cammaerts, Émile (1937). The Laughing Prophet: The Seven Virtues And G. K. Chesterton. London: Methuen & Co., Ltd.

- Campbell, W. E. (1908). "G.K. Chesterton: Inquisitor and Democrat," The Catholic World, Vol. LXXXVIII, pp. 769–782.

- Campbell, W. E. (1909). "G.K. Chesterton: Catholic Apologist" The Catholic World, Vol. LXXXIX, No. 529, pp. 1–12.

- Chesterton, Cecil (1908). G.K. Chesterton: A Criticism. London: Alston Rivers (Rep. by John Lane Company, 1909).

- Clipper, Lawrence J. (1974). G.K. Chesterton. New York: Twayne Publishers.

- Coates, John (1984). Chesterton and the Edwardian Cultural Crisis. Hull University Press.

- Coates, John (2002). G.K. Chesterton as Controversialist, Essayist, Novelist, and Critic. N.Y.: E. Mellen Press

- Conlon, D. J. (1987). G.K. Chesterton: A Half Century of Views. Oxford University Press.

- Cooney, A (1999), G.K. Chesterton, One Sword at Least, London: Third Way, ISBN 0-9535077-1-8.

- Coren, Michael (2001) [1989], Gilbert: The Man who was G.K. Chesterton, Vancouver: Regent College Publishing, ISBN 9781573831956, OCLC 45190713.

- Corrin, Jay P. (1981). G.K. Chesterton & Hilaire Belloc: The Battle Against Modernity. Ohio University Press.

- Ervine, St. John G. (1922). "G.K. Chesterton." In: Some Impressions of my Elders. New York: The Macmillan Company, pp. 90–112.

- Ffinch, Michael (1986), G.K. Chesterton, Harper & Row.

- Hitchens, Christopher (2012). "The Reactionary," The Atlantic.

- Herts, B. Russell (1914). "Gilbert K. Chesterton: Defender of the Discarded." In: Depreciations. New York: Albert & Charles Boni, pp. 65–86.

- Hollis, Christopher (1970). The Mind of Chesterton. London: Hollis & Carter.

- Hunter, Lynette (1979). G.K. Chesterton: Explorations in Allegory. London: Macmillan Press.

- Jaki, Stanley (1986). Chesterton: A Seer of Science. University of Illinois Press.

- Jaki, Stanley (1986). "Chesterton's Landmark Year." In: Chance or Reality and Other Essays. University Press of America.

- Kenner, Hugh (1947). Paradox in Chesterton. New York: Sheed & Ward.

- Ker, Ian (2011), G. K, Chesterton: A Biography, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-960128-8

- Kimball, Roger (2011). "G. K. Chesterton: Master of Rejuvenation," The New Criterion, Vol. XXX, p. 26.

- Kirk, Russell (1971). "Chesterton, Madmen, and Madhouses," Modern Age, Vol. XV, No. 1, pp. 6–16.

- Knight, Mark (2004). Chesterton and Evil. Fordham University Press.

- Lea, F.A. (1947). "G. K. Chesterton." In: Donald Attwater (ed.) Modern Christian Revolutionaries. New York: Devin-Adair Co.

- McCleary, Joseph R. (2009). The Historical Imagination of G.K. Chesterton: Locality, Patriotism, and Nationalism. Taylor & Francis.

- McLuhan, Marshall (1936), "GK Chesterton: A Practical Mystic", Dalhousie Review, 15 (4).

- McNichol, J. (2008), The Young Chesterton Chronicles, Book One: The Tripods Attack!, Manchester, NH: Sophia Institute, ISBN 978-1-933184-26-5.

- Oddie, William (2010). Chesterton and the Romance of Orthodoxy: The Making of GKC, 1874–1908. Oxford University Press.

- Orage, Alfred Richard. (1922). "G.K. Chesterton on Rome and Germany." In: Readers and Writers (1917–1921). London: George Allen & Unwin, pp. 155–161.

- Oser, Lee (2007). The Return of Christian Humanism: Chesterton, Eliot, Tolkien, and the Romance of History. University of Missouri Press.

- Paine, Randall (1999), The Universe and Mr. Chesterton, Sherwood Sugden, ISBN 0-89385-511-1.

- Pearce, Joseph (1997), Wisdom and Innocence – A Life of GK Chesterton, Ignatius Press, ISBN 978-0-89870-700-7.

- Peck, William George (1920). "Mr. G.K. Chesterton and the Return to Sanity." In: From Chaos to Catholicism. London: George Allen & Unwin, pp. 52–92.

- Raymond, E. T. (1919). "Mr. G.K. Chesterton." In: All & Sundry. London: T. Fisher Unwin, pp. 68–76.

- Schall, James V. (2000). Schall on Chesterton: Timely Essays on Timeless Paradoxes. Catholic University of America Press.

- Scott, William T. (1912). Chesterton and Other Essays. Cincinnati: Jennings & Graham.

- Seaber, Luke (2011). G.K. Chesterton's Literary Influence on George Orwell: A Surprising Irony. New York: Edwin Mellen Press.

- Sheed, Wilfrid (1971). "Chesterbelloc and the Jews," The New York Review of Books, Vol. XVII, No. 3.

- Shuster, Norman (1922). "The Adventures of a Journalist: G.K. Chesterton." In: The Catholic Spirit in Modern English Literature. New York: The Macmillan Company, pp. 229–248.

- Slosson, Edwin E. (1917). "G.K. Chesterton: Knight Errant of Orthodoxy." In: Six Major Prophets. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, pp. 129–189.

- Smith, Marion Couthouy (1921). "The Rightness of G.K. Chesterton," The Catholic World, Vol. CXIII, No. 678, pp. 163–168.

- Stapleton, Julia (2009). Christianity, Patriotism, and Nationhood: The England of G.K. Chesterton. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

- Sullivan, John (1974), G.K. Chesterton: A Centenary Appraisal, London: Paul Elek, ISBN 0-236-17628-5.

- Tonquédec, Joseph de (1920). G.K. Chesterton, ses Idées et son Caractère, Nouvelle Librairie National.

- Ward, Maisie (1944), Gilbert Keith Chesterton, Sheed & Ward.

- Ward, Maisie (1952). Return to Chesterton, London: Sheed & Ward.

- West, Julius (1915). G.K. Chesterton: A Critical Study. London: Martin Secker.

- Williams, Donald T (2006), Mere Humanity: G.K. Chesterton, CS Lewis, and JRR Tolkien on the Human Condition.

Pranala luar

| Cari tahu mengenai G.K. Chesterton pada proyek-proyek Wikimedia lainnya: | |

| Gambar dan media dari Commons | |

| Kutipan dari Wikiquote | |

| Teks sumber dari Wikisource | |

| Entri basisdata #Q183167 di Wikidata | |

- Bibliowiki memiliki media atau teks asli yang berkaitan dengan artikel ini: Gilbert Keith Chesterton (domain publik di Kanada)

- G.K. Chesterton di Curlie (dari DMOZ)

- Karya G. K. Chesterton di Project Gutenberg

- Karya G. K. (Gilbert Keith) Chesterton di Faded Page (Canada)

- Karya oleh/tentang G.K. Chesterton di Internet Archive (pencarian dioptimalkan untuk situs non-Beta)

- Karya G.K. Chesterton di LibriVox (buku suara domain umum)

- Works by G.K. Chesterton, at HathiTrust

- "Materi arsip tentang G.K. Chesterton". UK National Archives.

- What's Wrong: GKC in Periodicals Articles by G. K. Chesterton in periodicals, with critical annotations.

- The American Chesterton Society, diakses tanggal 28 October 2010.

- G. K. Chesterton: Quotidiana

- G.K. Chesterton research collection Diarsipkan 2017-08-16 di Wayback Machine. at The Marion E. Wade Center at Wheaton College

- G.K. Chesterton Archival Collection Diarsipkan 2015-10-29 di Wayback Machine. at the University of St. Michael's College at the University of Toronto