Apokalipsis Petrus

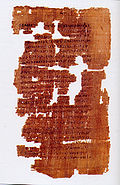

Apokalipsis Petrus[note 1] atau Wahyu kepada Petrus adalah karya sastra Kristen Purba abad ke-2 dan karya sastra apokalipsis. Karya sastra ini merupakan dokumen yang paling awal ditulis dan masih lestari sampai sekarang, yang menggambarkan surga dan neraka versi Kristen secara terperinci. Apokalipsis Petrus dipengaruhi sastra apokalipsis Yahudi maupun filsafat Helenistis dari kebudayaan Yunani. Karya sastra ini terlestarikan dalam dua versi berlainan dari satu karya asli dalam Yunani-Koine yang sudah musnah, yaitu versi Yunani yang lebih pendek dan versi Habasyi yang lebih panjang.

| Bagian dari seri |

| Apokrifa Perjanjian Baru |

|---|

|

|

|

Apokalipsis Petrus adalah karya tulis pseudepigraf, digadang-gadang sebagai karya tulis murid Petrus, tetapi penulis yang sesungguhnya tidak diketahui. Di dalamnya termuat penjabaran penglihatan gaib yang dialami Petrus melalui Kristus. Sesudah mengulik tanda-tanda kedatangan Kristus kali kedua, karya tulis ini mulai menjabarkan penglihatan gaib tentang akhirat (katabasis) serta memerinci aneka pahala nikmat surgawi yang diperuntukkan bagi orang-orang benar maupun aneka ganjaran siksa neraka yang diperuntukkan bagi orang-orang terlaknat. Siksa neraka secara khusus digambarkan dengan sangat hidup lagi jasmaniah, dan kurang-lebih sejalan dengan asas "mata ganti mata" (lex talionis). Penghujat dibuat bergelantung dengan lidahnya, saksi dusta ditebas bibirnya, hartawan bakhil dibuat berpakaian compang-camping seperti pengemis dan ditembuk batu-batu tajam lagi panas membara, dan seterusnya.

Meskipun tidak dimasukkan ke dalam kanon baku Perjanjian Baru, Apokalipsis Petrus tergolong karya sastra Apokrifa Perjanjian Baruapokrifa Perjanjian Baru, dan tersenarai di dalam kanon fragmen Muratori, yakni daftar kitab Kristen berterima dari abad ke-2 yang merupakan salah satu purwa-kanon tertua yang masih lestari sampai sekarang. Meskipun demikian, fragmen Muratori mengungkapkan keragu-raguannya akan ketulenan Apokalipsis Petrus dengan mengemukakan bahwa beberapa pihak berwenang tidak akan mengizinkan karya tulis itu dibacakan di dalam gereja. Meskipun memengaruhi berbagai karya sastra Kristen lain yang ditulis pada abad ke-2, ke-3, dan ke-4, Apokalipsis Petrus akhirnya dicap gadungan dan lambat laun ditinggalkan orang, kalah pamor dari Apokalipsis Paulus, karya sastra abad ke-4 yang sarat dengan pengaruh dari Apokalipsis Petrus lantaran menjabarkan penglihatan gaib yang sudah dimutakhirkan tentang surga dan negara. Apokalipsis Petrus merupakan contoh karya tulis dari ragam sastra yang sama dengan Divina Comedia karangan Dante yang terkenal itu, yakni ragam sastra yang mengisahkan petualangan tokoh utamanya ke alam akhirat.

Perkitaan waktu penulisan

Apokalipsis Petrus tampaknya ditulis dalam rentang perkiraan waktu tahun 100 sampai 150 tarikh Masehi. Terminus post quem-nya, yakni batas akhir rentang pekiraan waktu penulisan Apokalipsis Petrus, ditetapkan berdasarkan kesan yang tampak bahwa kemungkinan besar karya tulis ini mengutip nas-nas 4 Ezra, karya sastra yang ditulis sekitar tahun 100 tarikh Masehi.[5] Nas-nas Apokalipsis Petrus dikutip di dalam Parwa ke-2 Orakel Sibila (sekitar tahun 150), dan disebutkan namanya maupun dikutip nas-nasnya di dalam risalah Klemens dari Aleksandria yang bertajuk Petikan-Petikan Nubuat (sekitar tahun 200).[6] Namanya juga tercantum di dalam fragmen Muratori yang lazim diperkirakan berasal dari seperempat akhir abad ke-2 (sekitar tahun 170–200).[7] Semua fakta di atas mengisyaratkan bahwa Apokalipsis Petrus sudah ada sekitar tahun 150 tarikh Masehi.[8]

Richard Bauckham mengusulkan rentang perkiraan waktu yang lebih sempit, yaitu rentang waktu pemberontakan Bar Kokba (tahun 132–136), dan menduga penulisnya adalah seorang Kristen Yahudi yang berdiam di |Yudea jajahan Romawi, daerah yang terdampak oleh pemberontakan tersebut.[note 2] Sarjana-sarjana lain mengusulkan Mesir jajahan Romawi sebagai perkiraan tempat penulisannya.[note 3]

Sejarah naskah

Dari Abad Pertengahan sampai tahun 1886, keberadaan Apokalipsis Petrus hanya diketahui melalui kutipan-kutipan dan penyebutan-penyebutan judulnya di dalam karya-karya sastra Kristen Purba.[13]

- Those who lend money and charge interest stand up to their knees in a lake of foul matter and blood.

- Men who take on the role of women in a sexual way, and lesbians, fall from the precipice of a great cliff repeatedly.

- Makers of idols either scourge themselves with fire whips (Ethiopic) or they beat each other with fire rods (Akhmim).

- Those who forsook God's commandments and heeded demons burn in flames.

- Those who do not honor their parents fall into a stream of fire repeatedly.

- Those who do not heed the counsel of their elders are attacked by flesh-devouring birds.

- Women who had premarital sex have their flesh torn to pieces.

- Disobedient slaves gnaw their tongues unceasingly.

- Those who give alms hypocritically are rendered blind and deaf, and fall upon coals of fire.

- Sorcerers are hung on a wheel of fire.[14][15][16]

}}

The vision of heaven is shorter than the depiction of hell, and described more fully in the Akhmim version. In heaven, people have pure milky white skin, curly hair, and are generally beautiful. The earth blooms with everlasting flowers and spices. People wear shiny clothes made of light, like the angels. Everyone sings in choral prayer.[17][18]

In the Ethiopic version, the account closes with an account of the ascension of Jesus on the mountain in chapters 15–17. Jesus, accompanied by the prophets Moses and Elijah, ascends on a cloud to the first heaven, and then they depart to the second heaven. While it is an account of the ascension, it includes some parallels to Matthew's account of the transfiguration of Jesus.[19] In the Akhmim fragment, which is set when Jesus was still alive, both the mountain and the two other men are unnamed (rather than being Moses and Elijah), but the men are similarly transfigured into radiant forms.[20]

Prayers for those in hell

One theological issue of note appears only in the version of the text in the Rainer fragment. Its chapter 14 describes the salvation of condemned sinners for whom the righteous pray:[21]

Then I will grant to my called and elect ones whomsoever they request from me, out of the punishment. And I will give them [i.e. those for whom the elect pray] a fine baptism in salvation from the Acherousian lake which is, they say, in the Elysian field, a portion of righteousness with my holy ones.[21]

While not found in later manuscripts, this reading was likely original to the text, as it agrees with a quotation in the Sibylline Oracles:[21]

To these pious ones imperishable God, the universal ruler, will also give another thing. Whenever they ask the imperishable God to save men from the raging fire and deathless gnashing he will grant it, and he will do this. For he will pick them out again from the undying fire and set them elsewhere and send them on account of his own people to another eternal life with the immortals in the Elysian plain where he has the long waves of the deep perennial Acherusian lake.

— Sibylline Oracles, Book 2, 330–338[22]

Other pieces of Christian literature with parallel passages probably influenced by this include the Epistle of the Apostles and the Coptic Apocalypse of Elijah.[23][note 4] The passage also makes literary sense, as it is a follow-up to a passage in chapter 3 where Jesus initially rebukes Peter who expresses horror at the suffering in hell; Richard Bauckham suggests that this is because it must be the victims who were harmed that request mercy, not Peter. While not directly endorsing universal salvation, it does suggest that salvation will eventually reach as far as the compassion of the elect.[21]

The Ethiopic manuscript maintains a version of the passage, but it differs in that it is the elect and righteous who receive baptism and salvation in a field rather than a lake ("field of Akerosya, which is called Aneslasleya" in Ethiopic), perhaps conflating Acherusia with the Elysian field.[26] The Ethiopic version of the list of punishments in hell includes sentences not in the Akhmim fragment saying that the punishment is eternal—hypothesized by many scholars to be later additions.[27] Despite this, the other Clementine works in the Ethiopic manuscripts discuss a great act of divine mercy to come that must be kept secret, yet will rescue some or all sinners from hell, suggesting this belief had not entirely fallen away.[28][29][30]

Influences, genre, and related works

As the title suggests, the Apocalypse of Peter is classed as part of apocalyptic literature in genre. The Greek word apokalypsis literally means "revelation", and apocalypses typically feature a revelation of otherworldly secrets from a divine being to a human—in the case of this work, Jesus and Peter.[31] Like many other apocalypses, the work is pseudepigraphal: it claims the authorship of a famous figure to bolster the authority of its message.[32] The Apocalypse of Peter is one of the earliest examples of a Christian–Jewish katabasis, a genre of explicit depictions of the realms and fates of the dead.[33]

Predecessors

Much of the original scholarship on the Apocalypse was on determining its predecessor influences. The first studies generally emphasized its roots in Hellenistic philosophy and thought. Nekyia, a work by Albrecht Dieterich published in 1893 on the basis of the Akhmim manuscript alone, identified parallels and links with the Orphic religious tradition and Greek cultural context.[34] Plato's Phaedo is often held as a major example of the forerunning Greek beliefs on the nature of the afterlife that influenced the Apocalypse of Peter.[18] Later scholarship by Martha Himmelfarb and others has emphasized the strong Jewish roots of the Apocalypse of Peter as well; it seems that apocalypses were a popular genre among Jews in the era of Greek and then Roman rule. Much of the Apocalypse of Peter may be based on or influenced by these lost Jewish apocalypses, works such as the "Book of the Watchers" (chapters 1–36 of the Book of Enoch), and 1st–2nd-century Jewish thought in general.[35][2] The book probably cites the Jewish apocalyptic work 4 Esdras.[5] The author also appears to be familiar with the Gospel of Matthew and no other; a line in chapter 16 has Peter realizing the meaning of the Beatitude quote that "Blessed are those who are persecuted for righteousness's sake, for theirs is the kingdom of Heaven."[36]

The Apocalypse of Peter seems to quote from Ezekiel 37, the story of the Valley of Dry Bones. During its rendition of the ascension of Jesus, it also quotes from Psalm 24, which was considered as a messianic psalm foretelling the coming of Jesus and Christianity in the early church. The psalm is given a cosmological interpretation as a prophecy of Jesus's entry into heaven.[37]

The post-mortem baptism in the Acherousian lake was likely influenced by the Jewish cultural practice of washing the dead before the corpse is buried, a practice shared by early Christians. There was a linkage or analogy between cleansing the soul on death as well as cleaning the body, as the Apocalypse of Peter passage essentially combines the two.[26]

While much work has been done on predecessor influences, Eric Beck stresses that much of the Apocalypse of Peter is distinct among extant literature of the period, and may well have been unique at the time, rather than simply adapting lost earlier writings.[38] As an example, earlier Jewish literature varied in its depictions of Sheol, the underworld, but did not usually threaten active torment to the wicked. Instead eternal destruction was the more frequent threat in these early works, a possibility that does not arise in the Apocalypse of Peter.[39]

Contemporary work

The opening of the book has the resurrected Jesus giving further insights to the Apostles, followed by an account of Jesus's ascension. This appears to have been a popular setting in 2nd century Christian works, and the dialogue generally took place on a mountain, as in the Apocalypse of Peter. The genre is sometimes called a "dialogue Gospel", and is seen in works such as the Epistle of the Apostles, the Questions of Bartholomew, and various Gnostic works such as the Pistis Sophia.[36]

Among writings that were eventually canonized in the New Testament, the Apocalypse of Peter shows a close resemblance in ideas with the epistle 2 Peter, to the extent that many scholars believe one had copied passages from the other due to the number of close parallels.[40][41] While both the Apocalypse of Peter and the Apocalypse of John (the Book of Revelation) are apocalypses in genre, the Revelation of Peter puts far more stress on the afterlife and divine rewards and punishments, while the Revelation of John focuses on a cosmic battle between good and evil.[42]

Later influence

The Apocalypse of Peter is the earliest surviving detailed depiction of heaven and hell in a Christian context. These depictions appear to have been quite influential to later works, although how much of this is due to the Apocalypse of Peter itself and how much due to lost similar literature is unclear.[8][35]

The Sibylline Oracles, popular among Roman Christians, directly quotes the Apocalypse of Peter.[44][45] Macarius Magnes's Apocriticus, a 3rd-century Christian apologetic work, features "a pagan philosopher" who quotes the Apocalypse of Peter, albeit in an attempt to disprove Christianity.[46] The visions narrated in the Acts of Thomas, a 3rd century work, also appear to quote or reference the Apocalypse of Peter.[47] The bishop Methodius of Olympus appears to positively quote the Apocalypse of Peter in the 4th century, although it is uncertain whether he regarded it as scripture.[48][note 5]

The Apocalypse of Peter is a predecessor of and has similarities with the genre of Clementine literature that would later be popular in Alexandria, despite Clement himself not appearing in the Apocalypse of Peter. Clementine stories usually involved Peter and Clement of Rome having adventures, revelations, and dialogues together. Both Ethiopic manuscripts that include the Apocalypse of Peter are mixed in with other Ethiopic Clementine literature that feature Peter prominently.[51] Clementine literature became popular in the third and fourth century, but it is not known when the Clementine sections of the Ethiopic manuscripts containing the Apocalypse of Peter were originally written. Daniel Maier proposes an Egyptian origin in the 6th–10th centuries as an estimate, while Richard Bauckham suggests the author was familiar with the Arabic Apocalypse of Peter and proposes an origin in the 8th century or later.[52][28]

Later apocalyptic works inspired by it include the Apocalypse of Thomas in the 2nd–4th century, and more influentially, the Apocalypse of Paul in the 4th century.[42][53] One tweak that the Apocalypse of Paul makes is describing personal judgments to bliss or torment that happen immediately after death, rather than the Apocalypse of Peter being a vision of a future destiny that will take place after the Second Coming of Jesus. Hell and paradise are both on a future Earth in Peter, but are another realm of existence in Paul.[48][54] The Apocalypse of Paul is also more interested in condemning sins committed by insufficiently devout Christians, while the Apocalypse of Peter seems to view the righteous as a unified group.[55] The Apocalypse of Paul never saw official Church approval. Despite this, it would go on to be popular and influential for centuries, possibly due to its popularity among the medieval monks that copied and preserved manuscripts in the turbulent centuries following the fall of the Western Roman Empire. Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy would become extremely popular and celebrated in the 14th century and beyond, and was influenced by the Apocalypse of Paul.[42][43] Directly or indirectly, the Apocalypse of Peter was the parent and grandparent of these influential visions of the afterlife.[3]

Analysis

The punishments and lex talionis

But the wicked and sinners and hypocrites will stand in the midst of a pit of darkness that cannot be extinguished and their punishment will be fire. And the angels will bring their sin and they will prepare for them a place where they will be punished forever, each one according to their transgression.

— Apocalypse of Peter (Ethiopic) 6:5-6[56]

The list of punishments for the damned is likely the most influential and famous part of the work, with almost two-thirds of the text dedicated to the calamitous end times that will accompany the return of Jesus (Chapters 4–6) and the punishments afterward (Chapters 7–13).[57][16] The punishments in the vision generally correspond to the past sinful actions, usually with a correspondence between the body part that sinned and the body part that is tortured.[15] It is a loose version of the Jewish notion of an eye for an eye, also known as lex talionis, that the punishment should fit the crime. The phrase "each according to his deed" appears five times in the Ethiopic version to explain the punishments.[58][57] Dennis Buchholz writes that the verse "Everyone according to his deeds" is the theme of the entire work.[59] In a dialogue with the angel Tatirokos, the keeper of Tartarus, the damned themselves admit from their own lips that their fate is based on their own deeds, and is fair and just, .[60][61] Still, the connection between the crime and the punishment is not always obvious. David Fiensy writes that "It is possible that where there is no logical correspondence, the punishment has come from the Orphic tradition and has simply been clumsily attached to a vice by a Jewish redactor."[62][63]

Bart Ehrman contests classifying the ethics of the Apocalypse as being those of lex talionis, and considers bodily correspondence the overriding concern instead. For Ehrman, the punishments described are far more severe than the original crime – which goes against the idea of punishments being commensurate to the damage inflicted within "an eye for an eye".[61]

Callie Callon suggests a philosophy of "mirror punishment" as motivating the punishments where the harm done is reflected in a sort of poetic justice, and is often more symbolic in nature. She argues that this best explains the logic behind placing sorcerers in a wheel of fire, long considered unclear. Other scholars have suggested that it is perhaps a weak reference to the punishment of Ixion in Greek mythology; Callon suggests that it is, instead, a reference to a rhombus, a spinning top that was also used by magicians. The magicians had spun a rhombus for power in their lives, and now were tormented by similar spinning, with the usual addition of fire seen in other punishments.[64][57]

The text is somewhat corrupt and unclear in Chapter 11, found only in the Ethiopic version, which describes the punishment for those who dishonor their parents. The nature of the first punishment is hard to discern and involves going up to a high fiery place, perhaps a volcano. It is believed by most translators that the target was closer to "adults who abandon their elderly parents" rather than condemning disobedient children, but it is difficult to be certain.[65] However, the next punishments do target children, saying that those who fail to heed tradition and their elders will be devoured by birds, while girls who do not maintain their virginity before marriage (implicitly also a violation of parental expectations) have their flesh torn apart. This is possibly an instance of mirror punishment or bodily correspondence, where the skin which sinned is itself punished. The text also specifies "ten" girls are punished – possibly a loose callback to the Parable of the Ten Virgins in the Gospel of Matthew, although not a very accurate one if so, as only five virgins are reprimanded in the parable, and for unrelated reasons.[66]

The Apocalypse of Peter is one of the earliest pieces of Christian literature to feature an anti-abortion message; mothers who abort their children are among those tormented.[67]

Christology

The Akhmim Greek text generally refers to Jesus as kyrios, "Lord". The Ethiopic manuscripts are similar, but the style notably shifts in Chapters 15 and 16 in the last section of the work, which refer to Jesus by name and introduce him with exalted titles including "Jesus Christ our King" (negus) and "my God Jesus Christ". This is considered a sign this section was edited later by a scribe with a high Christology.[68]

Angels and demons

It is unknown how much of the angelology and demonology in the Ethiopic version was in the older Greek versions. The Akhmim version does not mention demons when describing the punishment of those who forsook God's commandments; even in Ethiopic, it is possible that the demons are servants of God performing the punishment, rather than those who led the damned into sin. As the Ethiopic version was likely a translation of an Arabic translation, it may have picked up some influence from Islam centuries later; the references to Ezrael the Angel of Wrath were possibly influenced by Azrael the Angel of Death, who is usually more associated with Islamic angelology.[69][70] The Ethiopic version does make clear punishments are envisioned not just for human sin, but also supernatural evil: the angel Uriel gives physical bodies to the evil spirits that inhabited idols and led people astray so that they, too, can be burned in the fire and punished. Sinners who perished in the Great Flood are brought back as well: probably a reference to the Nephilim, the children of the Watchers (fallen angels) and mortal women described in the Book of Enoch, Book of Jubilees, and Genesis.[71]

The children who died to infanticide are delivered to the angel "Temelouchus", which probably was a rare Greek word meaning "care-taking [one]". Later writers seem to have interpreted it as a proper name, however, resulting in a specific angel of hell appearing named "Temlakos" (Ethipoic) or "Temeluchus" (Greek), found in the Apocalypse of Paul and various other sources.[60][72]

Literary merits

Scholars of the 19th and 20th century considered the work rather intellectually simple and naive; dramatic and gripping, but not necessarily a coherent story. Still, the Apocalypse of Peter was popular and had a wide audience in its time. M. R. James remarked that his impression was that educated Christians of the later Roman period considered the work somewhat embarrassing and "realized it was a gross and vulgar book", which might have partially explained a lack of elite enthusiasm for canonizing it later.[73][74]

Theology

The Second Coming of Christ and the resurrection of the dead, which he told to Peter, who die for their sin because they did not observe the commandment of God, their creator. And this he [Peter] reflected upon so that he might understand the mystery of the Son of God, the merciful and lover of mercy.

— Prologue to the Apocalypse of Peter (Ethiopic)[75]

One of the theological messages of the Apocalypse of Peter is generally considered clear enough: the torments of hell are meant to encourage keeping a righteous path and to warn readers and listeners away from sin, knowing the horrible fate that awaits those who stray.[76] The work also responds to the problem of theodicy addressed in earlier writings such as Daniel: how can God allow persecution of the righteous on Earth and still be both sovereign and just? The Apocalypse says that everyone will be repaid by their deeds, even the dead, and God will eventually make things right.[58] Scholars have come up with different interpretations of the intended tone of the work. Michael Gilmour sees the work as encouraging schadenfreude and delighting in the suffering of the wicked, while Eric Beck argues the reverse: that the work was intended to ultimately cultivate compassion for those suffering, including the wicked and even persecutors.[77][78] Most scholars agree that the Apocalypse simultaneously advocates for both divine justice and divine mercy, and contains elements of both messages.[63][79]

The version of the Apocalypse seen in the Ethiopic version could plausibly have originated from a Christian community that still considered itself as part of Judaism.[9][80] The adaptation of the fig tree parables to an allegory about the flourishing of Israel and its martyrs pleasing God is only found in Chapter 2 of the Ethiopic version, and is not in the Greek Akhmim version. While it is impossible to know why for sure, one possibility is that it was edited out due to incipient anti-Jewish tensions in the church. A depiction of Jews converting and Israel being especially blessed may not have fit the mood in the 4th and 5th centuries of the Church as some Christians strongly repudiated Judaism.[32]

In one passage in Chapter 16, Peter offers to build three tabernacles on Earth. Jesus sharply rebukes him, saying that there is only a single heavenly tabernacle. This is possibly a reference to the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 AD and a condemnation of attempting to build a replacement "Third Temple",[81] although perhaps it is only a reference to all of God's elect living together with a unified tabernacle in Paradise.[11]

Debate over canonicity

The Apocalypse of Peter was ultimately not included in the New Testament, but appears to have been one of the works that came closest to being included, along with The Shepherd of Hermas.[1]

The Muratorian fragment is one of the earliest-created extant lists of approved Christian sacred writings, part of the process of creating what would eventually be called the New Testament. The fragment is generally dated to the last quarter of the 2nd century (ca 170–200 AD). It gives a list of works read in the Christian churches that is similar to the modern accepted canon; however, it does not include some of the general epistles, but does include the Apocalypse of Peter. The Muratorian fragment states: "We receive only the apocalypses of John and Peter, though some of us are not willing that the latter be read in the church."[7] (Other pieces of apocalyptic literature are implicitly acknowledged, yet not "received".) Both the Apocalypse of Peter and the Apocalypse of John appear to have been controversial, with some churches of the 2nd and 3rd centuries using them and others not. Clement of Alexandria appears to have considered the Apocalypse of Peter to be holy scripture (ca 200 AD).[6] Eusebius personally classified the work as spurious, yet not heretical, in his book Church History (ca 320s AD). Eusebius also describes a lost work of Clement's, the Hypotyposes (Outlines), that gave "abbreviated discussions of the whole of the registered divine writings, without passing over the disputed [writings] – I mean Jude and the rest of the general letters, and the Letter of Barnabas, and the so-called Apocalypse of Peter."[82][83] The Apocalypse of Peter is listed in the catalog of the 6th-century Codex Claromontanus, which was probably copying a 3rd- or 4th-century source.[84] The Byzantine-era Stichometry of Nicephorus lists both the Apocalypses of Peter and John as used if disputed books.[32]

Although these references to it attest that it was in wide circulation in the 2nd century, the Apocalypse of Peter was ultimately not accepted into the Christian biblical canon. The reason why is not entirely clear, although considering the reservations various church authors had on the Apocalypse of John (the Book of Revelation), it is possible similar considerations were in play. As late as the 5th century, Sozomen indicates that some churches in Palestine still read it, but by then, it seems to have been considered inauthentic by most Christians.[85][48]

One hypothesis for why the Apocalypse of Peter failed to gain enough support to be canonized is that its view on the afterlife was too close to endorsing Christian universalism and the related doctrine of apokatastasis, that God will make all things perfect in the fullness of time.[86] The passage in the Rainer fragment that the saints, seeing the torment of sinners from heaven, could ask God for mercy, and these damned souls could be retroactively baptized and saved, had significant theological implications. Presumably, all of hell could eventually be emptied in such a manner; M. R. James suggested that the original Apocalypse of Peter may well have suggested universal salvation after a period of cleansing suffering in hell.[8][87] This ran against the stance of many Church theologians of the 3rd, 4th, and 5th centuries who strongly felt that salvation and damnation were eternal and strictly based on actions and beliefs while alive. Augustine of Hippo, in his work The City of God, denounces arguments based on very similar logic to what is seen in the Rainer passage.[88] Such a system, where saints could at least pray their friends and family out of hell, and possibly any damned soul, would have been considered incorrect at best, and heretical at worst to these views. Most scholars since agree with James: the reading in the Rainer fragment was that of the original.[89] The contested passage was not copied by later scribes who felt it was in error, hence not appearing in later manuscripts, along with the addition of the sentences indicating the punishment would be eternal. Bart Ehrman suggests that the damage to the book's reputation was already done, however. The Origenist Controversies of the 4th and 5th centuries retroactively condemned much of the thought of the theologian Origen, particularly his belief in universal salvation, and this anti-Origen movement was at least part of why the book was not included in the biblical canons of later centuries.[90][note 6]

Translations

Selected modern English translations of the Apocalypse of Peter can be found in:[92]

- Beck, Eric J. (2019). Frey, Jörg, ed. Justice and Mercy in the Apocalypse of Peter: A New Translation and Analysis of the Purpose of the Text. WUNT 427. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. hlm. 66–73. ISBN 978-3-16-159030-6. (a composite translation drawing from both the Greek and the Ethiopic; available openly at pages 98–112 of Beck's thesis)

- Beck, Eric J. (2024). "Translation of the Ethiopic Apocalypse of Peter including the Pseudo-Clementine Framework". Dalam Maier, Daniel C.; Frey, Jörg; Kraus, Thomas J. The Apocalypse of Peter in Context (PDF). Studies on Early Christian Apocrypha 21. Peeters. hlm. 377–400. doi:10.2143/9789042952096 . ISBN 978-90-429-5208-9. (a translation of solely the Ethiopic text; available open-access)

- Buchholz, Dennis D. (1988). Your Eyes Will Be Opened: A Study of the Greek (Ethiopic) Apocalypse of Peter. Society of Biblical Literature Dissertation series 97. Atlanta: Scholars Press. hlm. 157–244. ISBN 1-55540-025-6.

- Elliott, James Keith (1993). The Apocryphal New Testament. Oxford University Press. hlm. 593–615. ISBN 0-19-826182-9.

- Gardiner, Eileen (1989). Visions of Heaven and Hell Before Dante. New York: Italica Press. hlm. 1–12. ISBN 9780934977142.

- Kraus, Thomas J.; Nicklas, Tobias (2004). Das Petrusevangelium und die Petrusapokalypse: Die griechischen Fragmente mit deutscher und englischer Übersetzung [The Gospel of Peter and the Apocalypse of Peter: The Greek Fragments with German and English Translation]. GCS N.F. 11 (dalam bahasa Jerman and Inggris). Berlin: De Gruyter. hlm. 118–120. ISBN 978-3110176353.

-->

Keterangan

- ^ bahasa Yunani Kuno: Ἀποκαλύψει τοῦ Πέτρου, translit. Apokalýpsei toú Pétrou

- ^ Argumen Richard Bauckham untuk mendukung pendapat yang mengatakan bahwa penulisnya adalah seorang Kristen-Yahudi yang berdiam di Palestina semasa pemberontakan Bar Kokba berkecamuk adalah karya tulis tersebut menyinggung soal seorang mesias palsu yang belum ketahuan palsu. Penyebutan si mesias palsu sebagai "pendusta" mungkin saja adalah pelesetan nama asli Bar Kokba, yaitu Bar Kosiba, menjadi Bar Koziba, yang berarti "anak dusta". Yang lebih umum lagi, si penulis tampaknya menulis dari sudut pandang pihak yang teraniaya, lantaran ia mengutuk pihak-pihak yang merenggut nyawa para martir dengan dusta mereka, dan menyifatkan Bar Kokba sebagai orang yang menghukum dan membunuh umat Kristen.[1] Scholars who have found Bauckham's argument convincing include Oskar Skarsaune and Dennis Buchholz.[9][10] Usulan ini tidak diterima semua pihak. Eibert Tigchelaar menyanggah secara tertulis dengan menyifatkan argumen Richard Bauckham sebagai argumen yang tidak meyakinkan, lantaran bisa saja sumber ilham dibalik penulisannya adalah musibah-musibah lain seperti Perang Kitos (tahun 115–117) maupun aniaya-aniaya di tingkat lokal yang sudah dilupakan orang.[11] Para sarjana yang sependapat dengan Eibert Tigchelaar, antara lain adalah Eric Beck dan Tobias Nicklas.[12]

- ^ Jan Bremmer menduga bahwa jejak-jejak pengaruh filsafat Yunani menyiratkan bahwa penulis atau penyuntingnya berdiam di Mesir yang lebih terhelenisasi, sekalipun mengerjakan sebuah karya tulis bertema Palestina.[2][3] Klaus Berger dan C.D.G. Müller mendeteksi venerasi kepada Petrus yang sama di dalam karya-karya sastra Kristen Mesir lainnya, maupun rujukan kepada amalan-amalan budaya Mesir; penyebutan oleh Klemens dari Aleksandria mengisyaratkan bahwa karya tulis tersebut populer di Aleksandria, pusat kesusastraan Mesir.[4]

- ^ The Acts of Paul and Thecla is another work possibly influenced by the Rainer passage, although this connection is more contested. M. R. James detected a parallel in a passage where Thecla prays for the dead Falconilla to be delivered to heaven, but Dennis Buchholz writes that this only shows the author was familiar with similar material in the Christian tradition.[24][25]

- ^ A contested example of influence is in Theophilus of Antioch's Apology to Autolycus. Gilles Quispel and R. M. Grant argued that a line in it might be loosely quoting the Akhmim version of the Apocalypse of Peter: a description of an Eden-like place of light and exquisite plants. Dennis Buchholz considers this argument as not convincing; while it is possible Theophilus was familiar with the Apocalypse of Peter, descriptions of paradise involving both light and flowering plants were common in the era, and seen in common sources such as the Book of Enoch.[49][50]

- ^ Origen wrote in the 3rd century, long after the Apocalypse of Peter was created, and his theological rationale for universal salvation was different; nevertheless, later Christians often assumed Origen's influence was the source of this doctrine. A scribal note to a manuscript of the Sibylline Oracles on the matter of prayers for the dead reads: "Plainly false. For the fire which tortures the condemned will never cease. Even I would pray that this be so, though I am marked with very great scars of faults, which have need of very great mercy. But let babbling Origen be ashamed of saying that there is a limit to punishment."[22][91]

Rujukan

- ^ a b c Bauckham 1998, hlm. 160–161.

- ^ a b c Bremmer, Jan (2003). "The Apocalypse of Peter: Greek or Jewish?". Dalam Bremmer, Jan N.; Czachesz, István. The Apocalypse of Peter. Peeters. hlm. 1–14. ISBN 90-429-1375-4.

- ^ a b c d Bremmer, Jan (2009). "Christian Hell: From the Apocalypse of Peter to the Apocalypse of Paul". Numen. 56 (2/3): 298–302. doi:10.1163/156852709X405026. JSTOR 27793794.

- ^ a b Müller, Caspar Detlef Gustav (2003). "Apocalypse of Peter". Dalam Schneemelcher, Wilhelm. New Testament Apocrypha: Volume Two: Writings Relating to the Apostles; Apocalypses and Related Subjects. Diterjemahkan oleh Wilson, Robert McLachlan (edisi ke-Revisi). Louisville: Westminster Press. hlm. 620–625. ISBN 0-664-22722-8.

- ^ a b Maurer 1965, hlm. 664. Bandingkan bab 3 Apokalipsis Petrus dengan nas 2 Ezra 5:33-56 (yang disebut 4 Ezra adalah bagian dari kitab 2 Ezra dari bab 3 sampai tamat).

- ^ a b Buchholz 1988, hlm. 22-29.

James, M. R. (1924). The Apocryphal New Testament. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Wikisource. p. 506. [scan]

See 41.1-2, 48.1, and 49.1 of the Prophetical Extracts, which correspond with the Ethiopic text: Eclogae propheticae (Greek text). - ^ a b Metzger, Bruce (1987). The Canon of the New Testament: Its Origin, Development, and Significance. Oxford: Clarendon Press. hlm. 191–201, 305–307. ISBN 0-19-826954-4.

- ^ a b c Elliott, James Keith (1993). "The Apocalypse of Peter". The Apocryphal New Testament. Oxford University Press. hlm. 593–595. doi:10.1093/0198261829.003.0032. ISBN 0-19-826182-9.

- ^ a b Skarsaune, Oskar (2007). Skarsaune, Oskar; Hvalvik, Reidar, ed. Jewish Believers in Jesus. Hendrickson Publishers. hlm. 384–388. ISBN 978-1-56563-763-4.

- ^ Buchholz 1988, hlm. 277-278, 408-412.

- ^ a b Tigchelaar, Eibert (2003). "Is the Liar Bar-Kokhba? Considering the Date and Provenance of the Greek (Ethiopic) Apocalypse of Peter". Dalam Bremmer, Jan N.; Czachesz, István. The Apocalypse of Peter. Peeters. hlm. 63–77. ISBN 90-429-1375-4.

- ^ Beck 2019, hlm. 9-11, 175.

- ^ Beck 2019, hlm. 2.

- ^ Kesalahan pengutipan: Tag

<ref>tidak sah; tidak ditemukan teks untuk ref bernamabauckham164 - ^ a b Czachesz, István (2003). "The Grotesque Body in the Apocalypse of Peter". Dalam Bremmer, Jan N.; Czachesz, István. The Apocalypse of Peter. Peeters. hlm. 111–114. ISBN 90-429-1375-4.

- ^ a b Buchholz 1988, hlm. 306-311.

- ^ Beck 2019, hlm. 88-92.

- ^ a b Adamik, Tamás (2003). "The Description of Paradise in the Apocalypse of Peter". Dalam Bremmer, Jan N.; Czachesz, István. The Apocalypse of Peter. Peeters. hlm. 78–89. ISBN 90-429-1375-4.

- ^ Buchholz 1988, hlm. 362-375.

- ^ Beck 2019, hlm. 94-95, 100-102 argues these parallels to the transfiguration were later additions to the Ethiopic version, and the account is best understood as an ascension narrative; while Lapham 2004, hlm. 201-205 argues that the Ethiopic compiler has conflated the transfiguration and ascension together, but is mostly a transfiguration narrative.

- ^ a b c d Bauckham 1998, hlm. 145–146, 232–235.

- ^ a b Charlesworth, James, ed. (1983). "The Sibylline Oracles". The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha Volume 1. Diterjemahkan oleh Collins, John J. Doubleday. hlm. 353. ISBN 0-385-09630-5.

- ^ James 1931, hlm. 272-273; Buchholz 1988, hlm. 47-48, 58-62; Bauckham 1998, hlm. 147–148.

- ^ James, M. R. (April 1931). "The Rainer Fragment of the Apocalypse of Peter". The Journal of Theological Studies. os-XXXII (127): 270–279. doi:10.1093/jts/os-XXXII.127.270.

See Acts of Paul and Thecla, 28-29. - ^ Buchholz 1988, hlm. 51-53.

- ^ a b Copeland, Kirsti B. (2003). "Sinners and Post-Mortem 'Baptism' in the Acherusian Lake". Dalam Bremmer, Jan N.; Czachesz, István. The Apocalypse of Peter. Peeters. hlm. 91–107. ISBN 90-429-1375-4.

- ^ Beck 2019, hlm. 56; Buchholz 1988, hlm. 348-351, 385-386.

- ^ a b Bauckham 1998, hlm. 147–148.

- ^ Beck 2019, hlm. 156-159.

- ^ James, M. R. (1924). The Apocryphal New Testament. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Wikisource. p. 520. [scan]

- ^ Beck 2019, hlm. 22-25.

- ^ a b c Ehrman, Bart (2012). Forgery and Counterforgery: The Use of Literary Deceit in Early Christian Polemics. Oxford University Press. hlm. 457–465. ISBN 9780199928033.

- ^ Ehrman 2022, hlm. 1, 71-72.

- ^ Dieterich, Albrecht (1893). Nekyia: Beiträge zur Erklärung der neuentdeckten Petrusapokalypse [Nekyia: Contributions to the understanding of the newly-discovered Apocalypse of Peter] (dalam bahasa Jerman). Leipzig: B. G. Teubner.

- ^ a b Himmelfarb, Martha (1983). Tours of Hell: An Apocalyptic Form in Jewish and Christian Literature. University of Pennsylvania Press. hlm. 8–11, 16–17, 41–45, 66–69, 127, 169–171. ISBN 0-8122-7882-8.

- ^ a b Bauckham 1998, hlm. 168–176, 208–209.

- ^ Van Ruiten, Jacques (2003). "The Old Testament Quotations in the Apocalypse of Peter". Dalam Bremmer, Jan N.; Czachesz, István. The Apocalypse of Peter. Peeters. hlm. 158–173. ISBN 90-429-1375-4.

- ^ Beck 2019, hlm. 27-28, 79-80.

- ^ Jost, Michael R. (2024). "Judgment, Punishment, and Hell in the Dead Sea Scrolls and the Apocalypse of Peter". Dalam Maier, Daniel C.; Frey, Jörg; Kraus, Thomas J. The Apocalypse of Peter in Context (PDF). Studies on Early Christian Apocrypha 21. Peeters. hlm. 132–152. doi:10.2143/9789042952096 . ISBN 978-90-429-5208-9.

- ^ Templat:Ublcb

- ^ Bremmer, Jan (2024). "The Apocalypse of Peter, 2 Peter and Sibylline Oracles II. Alexandrian Debates?". Dalam Maier, Daniel C.; Frey, Jörg; Kraus, Thomas J. The Apocalypse of Peter in Context (PDF). Studies on Early Christian Apocrypha 21. Peeters. hlm. 153–177. doi:10.2143/9789042952096 . ISBN 978-90-429-5208-9.

- ^ a b c Kesalahan pengutipan: Tag

<ref>tidak sah; tidak ditemukan teks untuk ref bernamanta2 - ^ a b Silverstein, Theodore (1935). Visio Sancti Pauli: The history of the Apocalypse in Latin, together with nine texts. London: Christophers. hlm. 3–5, 91.

- ^ Specifically Sibylline Oracles Book 2, verse 225 and following. See Collins 1983, hlm. 350-353 for a translation.

- ^ Beck 2019, hlm. 84-88. Adamik 2003 is a dissenting opinion that suggests that the Sibylline Oracles are not quoting the Apocalypse of Peter, but later microscope analysis of the Rainer fragment has suggested that the alternative transcription Adamik's argument is based on is not accurate.

- ^ Buchholz 1988, hlm. 29-34

- ^ Buchholz 1988, hlm. 53-54. For a dissenting opinion, Martha Himmelfarb argues that both the Acts of Thomas and the Apocalypse of Peter are drawing on the same early Jewish traditions to explain the similarities. See Himmelfarb 1983, hlm. 12-13.

- ^ a b c Jakab, Attila (2003). "The Reception of the Apocalypse of Peter in Ancient Christianity". Dalam Bremmer, Jan N.; Czachesz, István. The Apocalypse of Peter. Peeters. hlm. 174–186. ISBN 90-429-1375-4.

- ^ Buchholz 1988, hlm. 48-50.

- ^ Quispel, G.; Grant, R.M. (1952). "Note On the Petrine Apocrypha". Vigiliae Christianae. 6 (1): 31–32. doi:10.1163/157007252X00047.

- ^ Pesthy, Monika (2003). "'Thy Mercy, O Lord, is in the Heavens; and thy Righteousness Reaches unto the Clouds'". Dalam Bremmer, Jan N.; Czachesz, István. The Apocalypse of Peter. Peeters. hlm. 40–51. ISBN 90-429-1375-4.

- ^ Maier, Daniel C. (2024). "The Ethiopic Pseudo-Clementine Framework of the Apocalypse of Peter: Chances and Challenges in the African Transmission Context". Dalam Maier, Daniel C.; Frey, Jörg; Kraus, Thomas J. The Apocalypse of Peter in Context (PDF). Studies on Early Christian Apocrypha 21. Peeters. hlm. 153–177. doi:10.2143/9789042952096 . ISBN 978-90-429-5208-9.

- ^ Buchholz 1988, hlm. 65-70.

- ^ Fiori, Emiliano B. (2024). "'Close and yet so faraway': The Apocalypse of Peter and the Apocalypse of Paul". Dalam Maier, Daniel C.; Frey, Jörg; Kraus, Thomas J. The Apocalypse of Peter in Context (PDF). Studies on Early Christian Apocrypha 21. Peeters. doi:10.2143/9789042952096 . ISBN 978-90-429-5208-9.

- ^ Beck 2019, hlm. 104-105.

- ^ Beck 2019, hlm. 68.

- ^ a b c Beck 2019, hlm. 125-140.

- ^ a b Bauckham 1998, hlm. 194–198.

- ^ Buchholz 1988, hlm. 276.

- ^ a b Bauckham 1998, hlm. 223–225.

- ^ a b Ehrman 2022, hlm. 78–80.

- ^ Fiensy, David (1983). "Lex Talionis in the 'Apocalypse of Peter'". The Harvard Theological Review. 76 (2): 255–258. doi:10.1017/S0017816000001334. JSTOR 1509504.

- ^ a b Lanzillotta, Lautaro Roig (2003). "Does Punishment Reward the Righteous? The Justice Pattern Underlying the Apocalypse of Peter". Dalam Bremmer, Jan N.; Czachesz, István. The Apocalypse of Peter. Peeters. hlm. 127–157. ISBN 90-429-1375-4.

- ^ Callon, Callie (2010). "Sorcery, Wheels, and Mirror Punishment in the Apocalypse of Peter". Journal of Early Christian Studies. 18 (1): 29–49. doi:10.1353/earl.0.0304.

- ^ Beck 2019, hlm. 137; Buchholz 1988, hlm. 217-219, 332-334.

- ^ Beck 2019, hlm. 137-138; Buchholz 1988, hlm. 219-221, 334-336.

- ^ Templat:Ublcb

- ^ Buchholz 1988, hlm. 363; Beck 2019, hlm. 90.

- ^ Beck 2019, hlm. 84-93.

- ^ Kesalahan pengutipan: Tag

<ref>tidak sah; tidak ditemukan teks untuk ref bernamaburge2010 - ^ Bauckham 1998, hlm. 204–205; Buchholz 1988, hlm. 302–306. See Chapter 6 of the Apocalypse of Peter, Enoch 15, Enoch 16, and Genesis 6:1-7:NRSV.

- ^ James, M. R. (1924). The Apocryphal New Testament. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Wikisource. p. 507. [scan]

- ^ James, M. R. (1915). "The Recovery of the Apocalypse of Peter". Dalam Headlam, Arthur C. Church Quarterly Review. 80. London. hlm. 28.

- ^ Ehrman 2022, hlm. 188–189; Bauckham 1998, hlm. 93.

- ^ Beck 2019, hlm. 66, 123.

- ^ Bauckham 1998, hlm. 226-227; Beck 2019, hlm. 177-178.

- ^ Beck 2019, hlm. 14-18, 114, 120, 123-124, 169, 175.

- ^ Gilmour, Michael J. (2006). "Delighting in the Sufferings of Others: Early Christian Schadenfreude and the Function of the Apocalypse of Peter". Bulletin for Biblical Research. 16 (1): 129–139. doi:10.2307/26424014. JSTOR 26424014.

- ^ Bauckham 1998, hlm. 132–148.

- ^ Lapham, Fred (2004). Peter: The Myth, the Man and the Writings: A study of the early Petrine tradition. T&T Clark International. hlm. 193–216. ISBN 0567044904.

- ^ Bauckham 1998, hlm. 190–194.

- ^ Eusebius of Caesarea (2019). "Book 6, Chapter 14". The History of the Church. Diterjemahkan oleh Schott, Jeremy M. Oakland, California: University of California Press. hlm. 297. ISBN 9780520964969.

- ^ Buchholz 1988, hlm. 36-38; Ehrman 2022, hlm. 182-183; Metzger 1987, hlm. 203-204.

- ^ Ehrman 2022, hlm. 183; Buchholz 1988, hlm. 40-41.

- ^ Buchholz 1988, hlm. 39-40.

- ^ Ramelli, Ilaria (2013). The Christian Doctrine of Apokatastasis. Supplements to Vigiliae Christianae 120. Leiden: Brill. hlm. 67–72. doi:10.1163/9789004245709. ISBN 978-90-04-24570-9.

- ^ Beck 2019, hlm. 159-163, 167-168.

- ^ Bauckham 1998, hlm. 157–159; Beck 2019, hlm. 176–177. According to Augustine, the saints in heaven will have their will fully aligned with God, and thus would never want to oppose God's will that the damned be punished, so they would never pray for the salvation of the damned as they do in the Apocalypse of Peter. See The City of God Book 21, Chapter 18 and Book 21, Chapter 24.

- ^ Bremmer 2024, hlm. 174; Ehrman 2022, hlm. 189–191; Beck 2019, hlm. 4, 54-55; Bauckham 1998, hlm. 145–146, 232–235; Buchholz 1988, hlm. 342-350, 356-357.

- ^ Templat:Ublcb

- ^ Bauckham 1998, hlm. 148; Ehrman 2022, hlm. 198–199.

- ^ Pardee, Cambry (February 2017). "Apocalypse of Peter". e-Clavis: Christian Apocrypha. Diakses tanggal 10 June 2024.

Kepustakaan

- Bauckham, Richard B. (1998). The Fate of the Dead: Studies on the Jewish and Christian Apocalypses. Supplements to Novum Testamentum 93. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 9781589832886.

- Beck, Eric J. (2019). Frey, Jörg, ed. Justice and Mercy in the Apocalypse of Peter: A New Translation and Analysis of the Purpose of the Text. WUNT 427. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. doi:10.1628/978-3-16-159031-3. ISBN 978-3-16-159030-6.

- Bremmer, Jan N.; Czachesz, István, ed. (2003). The Apocalypse of Peter. Studies on Early Christian Apocrypha 7. Peeters. ISBN 90-429-1375-4.

- Buchholz, Dennis D. (1988). Your Eyes Will Be Opened: A Study of the Greek (Ethiopic) Apocalypse of Peter. Society of Biblical Literature Dissertation series 97. Atlanta: Scholars Press. ISBN 1-55540-025-6.

- Ehrman, Bart (2022). Journeys to Heaven and Hell: Tours of the Afterlife in the Early Christian Tradition. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-25700-7.

- Maier, Daniel C.; Frey, Jörg; Kraus, Thomas J., ed. (2024). The Apocalypse of Peter in Context (PDF). Studies on Early Christian Apocrypha 21. Peeters. doi:10.2143/9789042952096 . ISBN 978-90-429-5208-9.

Pranala luar

- Karya yang berkaitan dengan Apocalypse of Peter di Wikisource, hasil terjemahan M. R. James di dalam buku The Apocryphal New Testament yang terbit tahun 1924, disertai kutipan-kutipan dari Orakel Sibila dan risalah-risalah Gereja Purba

- Apokalipsis Petrus (isi fragmen Akhmim yang berbahasa Yunani), dialihaksarakan oleh Mark Goodacre dari edisi Erich Klostermann (HTML, Word, PDF)

- "Apokalipsis Petrus", tinjauan dan kepustakaan oleh Cambry Pardee. NASSCAL: e-Clavis: Apokripfa Kristen.

- Daftar pustaka mengenai Apokalipsis Petrus, oleh Eileen Gardiner