Prasasti Kurkh

Prasasti Kurkh (bahasa Inggris: Kurkh Monolith; Kurkh Stela) adalah sebuah monumen yang dibuat oleh raja Asyur yang memuat catatan sejarah Pertempuran Qarqar di bagian akhirnya. Sekarang dipamerkan di British Museum, London, Inggris, tetapi asalnya ditemukan di desa orang Kurdi yang bernama Kurkh (Bahasa Turki: Üçtepe), dekat kota Bismil di provinsi Diyarbakır, Turki. Batu monolith ini tingginya 2,2 meter. Isinya mencakup sejarah tahun pertama sampai ke-6 pemerintahan raja Asyur, Salmaneser III (859-824 SM), meskipun tahun ke-5 tidak ada.

Prasasti ini khususnya memuat penyerangan Salmaneser di bagian barat Mesopotamia dan Syria, bertempur dahsyat dengan negara-negara Beth Eden (Bit Adini) dan Karkemis. Di bagian akhir monolith ini tercantum riwayat "Pertempuran Qarqar", di mana gabungan dua belas raja bertempur melawan Salmaneser di kota Qarqar, Siria. Pasukan gabungan ini dipimpin oleh Irhuleni raja Hamat dan Hadadezer raja Damaskus, termasuk juga tentara berjumlah besar[1] pimpinan raja Ahab dari Israel. Prasasti ini juga pertama kalinya memuat kisah orang Arab dalam sejarah dunia, menyertakan satu pasukan onta yang dipimpin oleh raja Gindibu. | align = right | direction = horizontal | width = | footer = First published transcriptions, by George Smith (assyriologist)

| image1 = Kurkh Ashurnasirpal II Inscription.jpg | width1 = 140 | alt1 = | caption1 = Ashurnasirpal II

| image2 = Kurkh Shalmaneser III Inscription.jpg | width2 = 150 | alt2 = | caption2 = Shalmaneser III }}

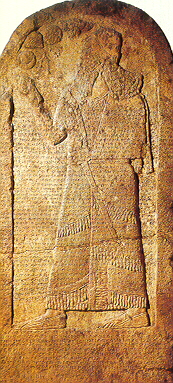

The stela depicting Shalmaneser III is made of limestone with a round top. It is 221 centimeters tall, 87 centimeters wide, and 23 centimeters deep.[2]

The British Museum describes the image as follows:

The king, Shalmaneser III, stands before four divine emblems: (1) the winged disk, the symbol of the god Ashur, or, as some hold, of Shamash; (2) the six-pointed star of Ishtar, goddess of the morning and evening star; (3) the crown of the sky-god Anu, in this instance with three horns, in profile; (4) the disk and crescent of the god Sin as the new and the full moon. On his collar the king wears as amulets (1) the fork, the symbol of the weather-god, Adad; (2) a segment of a circle, of uncertain meaning; (3) an eight-pointed star in a disk, here probably the symbol of Shamash, the sun-god; (4) a winged disk, again of the god Ashur. The gesture of the right hand has been much discussed and variously interpreted, either as the end of the action of throwing a kiss as an act of worship, or as resulting from cracking the fingers with the thumb, as a ritual act which is attributed to the Assyrians by later Greek writers, or as being simply a gesture of authority suitable to the king, with no reference to a particular religious significance. It seems fairly clear that the gesture is described in the phrase 'uban damiqti taraṣu', 'to stretch out a favourable finger', a blessing which corresponds to the reverse action, in which the index finger is not stretched out. There is a cuneiform inscription written across the face and base and around the sides of the stela.[2]

The inscription "describes the military campaigns of his (Shalmaneser III's) reign down to 853 BC."[3]

The stela depicting Ashurnasirpal II is made of limestone with a round top. It is 193 centimeters tall, 93 centimeters wide, and 27 centimeters deep. According to the British Museum, the stela "shows Ashurnasirpal II in an attitude of worship, raising his right hand to symbols of the gods" and its inscription "describes the campaign of 879 when Assyrians attacked the lands of the upper Tigris, in the Diyabakir region."[4]

Shalmaneser III Stela inscription

The inscription on the Shalmaneser III Stela deals with campaigns Shalmaneser made in western Mesopotamia and Syria, fighting extensively with the countries of Bit Adini and Carchemish. At the end of the Monolith comes the account of the Battle of Qarqar, where an alliance of twelve kings fought against Shalmaneser at the Syrian city of Qarqar. This alliance, comprising eleven kings, was led by Irhuleni of Hamath and Hadadezer of Damascus, describing also a large force[5] led by King Ahab of Israel.

The English translation of the end of the Shalmaneser III monolith is as follows:

Year 6 (Col. ll, 78-I02)

610. In the year of Dâian-Assur, in the month of Airu, the fourteenth day, I departed from Nineveh, crossed the Tigris, and drew near to the cities of Giammu, (near) the Balih(?) River. At the fearfulness of my sovereignty, the terror of my frightful weapons, they became afraid; with their own weapons his nobles killed Giammu. Into Kitlala and Til-sha-mâr-ahi, I entered. I had my gods brought into his palaces. In his palaces I spread a banquet. His treasury I opened. I saw his wealth. His goods, his property, I carried off and brought to my city Assur. From Kitlala I departed. To Kâr-Shalmaneser I drew near. In (goat)-skin boats I crossed the Euphrates the second time, at its flood. The tribute of the kings on that side of the Euphrates,---of Sangara of Carchemish, of Kundashpi of Kumuhu (Commagene), of Arame son of Gûzi, of Lalli the Milidean, of Haiani son of Gahari, of Kalparoda of Hattina, of Kalparuda of Gurgum, - silver, gold, lead, copper, vessels of copper, at Ina-Assur-uttir-asbat, on that side of the Euphrates, on the river Sagur, which the people of Hatti call Pitru, there I received (it). From the Euphrates I departed, I drew near to Halman (Aleppo). They were afraid to fight with (me), they seized my feet. Silver, gold, as their tribute I received. I offered sacrifices before the god Adad of Halman. From Halman I departed. To the cities of Irhulêni, the Hamathite, I drew near. The cities of Adennu, Bargâ, Arganâ, his royal cities, I captured. His spoil, his property, the goods of his palaces, I brought out. I set fire to his palaces. From Argana I departed. To Karkar I drew near.

611. Karkar, his royal city, I destroyed, I devastated, I burned with fire. 1,200 chariots, I,200 cavalry, 20,000 soldiers, of Hadad-ezer, of Aram (? Damascus); 700 chariots, 700 cavalry, 10,000* soldiers of Irhulêni of Hamath, 2,000 chariots, 10,000 soldiers of Ahab, the Israelite, 500 soldiers of the Gueans, 1,000 soldiers of the Musreans, 10 chariots, 10,000 soldiers of the Irkanateans, 200 soldiers of Matinuba'il, the Arvadite, 200 soldiers of the Usanateans, 30 chariots, [ ],000 soldiers of Adunu-ba'il, the Shianean, 1,000 camels of Gindibu', the Arabian, [ ],000 soldiers [of] Ba'sa, son of Ruhubi, the Ammonite, - these twelve kings he brought to his support; to offer battle and fight, they came against me. (Trusting) in the exalted might which Assur, the lord, had given (me), in the mighty weapons, which Nergal, who goes before me, had presented (to me), I battled with them. From Karkar, as far as the city of Gilzau, I routed them. 14,000 of their warriors I slew with the sword. Like Adad, I rained destruction upon them. I scattered their corpses far and wide, (and) covered (lit.., filled) the face of the desolate plain with their widespreading armies. With (my) weapons I made their blood to flow down the valleys(?) of the land. The plain was too small to let their bodies fall, the wide countryside was used up in burying them. With their bodies I spanned the Arantu (Orotes) as with a bridge(?). In that battle I took from them their chariots, their cavalry, their horses, broken to the yoke. (*Possibly 20,000).[6]

"Ahab of Israel"

The identification of "A-ha-ab-bu Sir-ila-a-a" with "Ahab of Israel" was first proposed[7] by Julius Oppert in his 1865 Histoire des Empires de Chaldée et d'Assyrie.[8]

Eberhard Schrader dealt with parts of the inscription on the Shalmaneser III Monolith in 1872, in his Die Keilinschriften und das Alte Testament ("Tulisan paku dan Perjanjian Lama").[9] The first full translation of the Shalmaneser III Monolith was provided by James Alexander Craig in 1887.[10]

Schrader wrote that the name "Israel" ("Sir-ila-a-a") was found only on this artifact in cuneiform inscriptions at that time, a fact which remains the case today. This fact has been brought up by some scholars who dispute the proposed translation.[11][12]

Schrader also noted that whilst Assyriologists such as Fritz Hommel[13] had disputed whether the name was "Israel" or "Jezreel",[9][14] because the first character is the phonetic "sir" and the place-determinative "mat". Schrader described the rationale for the reading "Israel", which became the scholarly consensus, as:

"the fact that here Ahab Sir'lit, and Ben-hadad of Damascus appear next to each other, and that in an inscription of this same king [Shalmaneser]'s Nimrud obelisk appears Jehu, son of Omri, and commemorates the descendant Hazael of Damascus, leaves no doubt that this Ahab Sir'lit is the biblical Ahab of Israel. That Ahab appears in cahoots with Damascus is quite in keeping with the biblical accounts, which Ahab concluded after the Battle of Aphek an alliance with Benhadad against their hereditary enemy Assyria."[9]

The identification was challenged by other contemporary scholars such as George Smith and Daniel Henry Haigh.[7]

The identification as Ahab of Israel has been challenged in more recent years by Werner Gugler and Adam van der Woude, who believe that "Achab from the monolith-inscription should be construed as a king from Northwestern Syria".[15]

According to the inscription, Ahab committed a force of 10,000 foot soldiers and 2,000 chariots to Assyrian led war coalition. The size of Ahab contribution indicates that the Kingdom of Israel was a major military power in the region of Syria-Palestine during the first half on 9th century BCE.[16]

Due to the size of Ahab army, which was presented as extraordinary large for ancient times, the translation raised polemics among scholars. Also, the usage of the term "Israel" was unique for Assyrian inscriptions, as the usual Assyrian terms for the Northern Kingdom of Israel were the "The Land of Omri" or Samaria.

According to Shigeo Yamada, the designation of a state by two alternative names is not unusual in the inscription of Shalmaneser.

Nadav Neeman proposed a scribal error in regard to the size of Ahab army and suggested that the army consisted of 200 instead of 2,000 chariots.

Summarizing scholarly works on this subject, Kelle suggests that the evidence "allows one to say that the inscription contains the first designation for the Northern Kingdom. Moreover, the designation "Israel" seems to have represented an entity that included several vassal states." The latter may have included Moab, Edom and Judah.[17] -->

Kesalahan tulisan dan perdebatan

Terdapat sejumlah dugaan kesalahan penulisan dalam prasasti ini, terutama berkisar dari Pertempuran Qarqar. Misalnya, di sana tertulis sebuah kota Gu-a-a, yang oleh beberapa pakar dianggap kota Quwê (Que). Namun, H. Tadmor yakin ini merupakan kesalahan tulis, yaitu Gu-a-a seharusnya Gu-bal-a-a, yang adalah kota Byblos. Lebih masuk akal jika Salmaneser memerangi Byblos dan bukannya Que, karena secara geografis lebih cocok di mana raja-raja lain berasal dari daerah di selatan dan barat Asyur, yang juga merupakan lokasi kota-negara Byblos, sedangkan Que, terletak di Silisia (Cilicia).

Juga diperdebatkan ejaan istilah musri, yang dalam bahasa Akkadia berarti "berbaris". Tadmor mengatakan bahwa orang Musri telah dikalahkan oleh Asyur di abad ke-11 SM, sehingga Musri di sini lebih tepat berarti "Mesir", tetapi sejumlah pakar tidak setuju dengan penafsiran ini.

Kesalahan teks lain adalah Kerajaan Asyur memerangi "dua belas raja". Di dalam prasasti itu nampaknya hanya terdaftar sebelas orang raja. Sejumlah pakar mencoba menjelaskan bahwa sesungguhnya ada raja ke-12 yang tersembunyi dalam istilah "Ba'sa orang dari Bit-Ruhubi, orang Amon". Seorang pakar mengusulkan pemisahan "Bit-Ruhubi" Beth-Rehob, sebuah negara di selatan Siria dan "Amon", sebuah negara di sisi timur sungai Yordan (Trans-Jordan). Namun istilah "dua belas raja" juga umum dipakai untuk menyebut "pasukan gabungan", sehingga mungkin saja pembuat prasasti itu menggunakan istilah itu sebagai kiasan, bukannya salah hitung.

Lihat pula

Referensi

- ^ Huffmon, Herbert B. "Jezebel - the 'Corrosive' Queen" in Joyce Rilett Wood, John E. Harvey, Mark Leuchter, eds. From Babel to Babylon: Essays on Biblical History And Literature in Honor of Brian Peckham, T&T Clark, 2006, ISBN 978-0-567-02892-1 p. 276 http://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=1Lvh29qOHHoC&oi=fnd&pg=PA273&dq=%22kurkh+monolith%22&ots=bjmQrTflBj&sig=k-0DuKWDrGxYo06Jcdk5mhZG1v0#PPA276,M1

- ^ a b British Museum. The Kurkh Stela: Shalmaneser III Accessed July 5, 2014

- ^ British Museum. Stela of Shalmaneser III Accessed July 5, 2014

- ^ British Museum. The Kurkh Stela: Ashurnasirpal II Accessed July 5, 2014

- ^ Huffmon, Herbert B. "Jezebel - the 'Corrosive' Queen" in Joyce Rilett Wood, John E. Harvey, Mark Leuchter, eds. From Babel to Babylon: Essays on Biblical History And Literature in Honor of Brian Peckham, T&T Clark, 2006, ISBN 978-0-567-02892-1 p. 276

- ^ Daniel David Luckenbill Ancient Records of Assyria and Babylonia (Chicago, 1926) Entire book is available online and to download here. Quoted text begins here. This is the English translation cited by the British Museum webpage on the Shalmaneser III stela here.

- ^ a b Assyrian Eponym Canon, George Smith, 1875, page 188-189, "The first one is called Ahab of Zirhala; and Professor Oppert, who discovered the name, reads Ahab the Israelite; but some ingenious remarks have been made on the name Zirhala by the Rev. D. H. Haigh, who has pointed out that Zir is not the usual reading of the first character, and that the name should be Suhala; and he suggests that the geographical name Samhala, or Savhala, a kingdom near Damascus, is intended in this place, and not the kingdom of Israel. The hypothesis of the Rev. D. H. Haigh may be correct; certainly he is right as to the usual phonetic value of the first character of this geographical name; but on the other hand, we find it certainly used sometimes for the syllable zir. Even if the view of the Rev. D. H. Haigh has to be given up, and if the reading, Ahab the Israelite, has to be accepted, it would be possible that this was not the Ahab of Scripture. The time when this battle took place, BC 854, was, according to the chronology here suggested, during the reign of Jehoahaz, king of Israel, BC 857 to 840; and at this time part of the territory of Israel had been conquered, and was held by the kingdom of Damascus: it is quite possible that the part of the country under the dominion of Damascus a ruler named Ahab may have reigned, and that he may have assisted Ben-hadad with his forces against the Assyrians. It does not seem likely that the Biblical Ahab, who was the foe of the king of Damascus, sent any troops to his aid, at least, such a circumstance is never hinted at in the Bible, and is contrary to the description of his conduct and reign. Under these circumstances I have given up the identification of the Ahab who assisted Ben-hadad at the battle of Qarqar, B.C. 854, with the Ahab, king of Israel, who died, I believe, forty-five years earlier, in BC 899."

- ^ Histoire des Empires de Chaldée et d'Assyrie, Julius Oppert, 1865, p.140, "La grande importance de ce texte réside dans la citation du roi célèbre par son impiété, et du nom d'Israël. On se souvient que le roi d'Assyrie cite juste sur l'obélisque, parmi ses tributaires, Jéhu, l'un des successeurs d'Achab, et contemporain de Hazaël qui paraît pour la première fois à la 18e campagne, tandis qu'à la 14e nous lisons encore le nom de son prédécesseur Benhadad."

- ^ a b c Eberhard Schrader, Die Keilinschriften und das Alte Testament, 1872 Quotes in German:

p58-59 "Der Name "Israel" selber findet sich und zwar als Name für das "Reich Israel" nur einmal in den Inschriften, nämlich auf dem neuentdeckten Stein Salmanassar's II, wo Ahab von Israel als Sir-'-lai d. i. als "der von Israel" bezeichnet wird (s. die Stelle in der Glosse zu 1 Kon. 16, 29). Es ist nun allerdings unter den Assyriologen Streit darüber, ob dieser Name wirklich mit hebr. ישראל und nicht vielmehr mit יזרעאל d. i. "Jezreel" zu identificiren sei, dieses deshalb, weil das erste Zeichen sonst den Lautwerth "sir" hat. Indess da das Adjectiv das Land-determinativ ("mat") vor sich hat, Jezreel aber kein "Land", denn vielmehr eine "Stadt" war, so wird schon deshalb die letztere Vermuthung aufzugeben sein. Dazu wird gerade bei zusammengesetzten, mit Zischlauten beginnenden Sylben ein so strenger Unterschied in den verschiedenen Zischlauten nicht gemacht, wie denn z. B. mit Bar-zi-pa in den Inschriften auch Bar-sip wechselt, obgleich sonst dem letzten Zeichen sip der andere "sip" fur gewohnlich nicht zukommt."

p99-100 "Der Umstand, dass hier Ahab, der Sir'lit, und Ben-hadad von Damaskus neben einander erscheinen, sowie dass dieser selbe Konig in der spater redigirten Inschrift des Nimrud obelisk's des Jehu ; Sohnes des Omri ; sowie anderseits des Hazael von Damask gedenkt, lässt darüber keinen Zweifel, dass unter diesem Ahab, dem Sir'lit en, der biblische Ahab von Israel gemeint ist. Dass aber Ahab im Bunde mit Damask erscheint; ist durchaus in Uebereinstimmung mit dem biblischen Berichte; wonach Ahab nach der Schlacht bei Aphek mit Benhadad ein Bündniss schloss, selbstverständlich gegen den Erbfeind von Damaskus , gegen Assyrien." - ^ The Monolith Inscription of Salmaneser II, (July 1, 1887), James A. Craig, Hebraica Volume: 3

- ^ Kesalahan pengutipan: Tag

<ref>tidak sah; tidak ditemukan teks untuk ref bernamabooks.google.co.uk - ^ Kelle 2002, hlm. 642a.

- ^ Hommel 1885, hlm. 609: "[beziehungsweise] Jesreel als seiner Residenz" ("or Jezreel as his residence")

- ^ Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament, p278-279

- ^ Becking 1999, hlm. 11: "No clear evidence then occurs for several centuries until the time of Shalmaneser III (9th century) who refers to 'Ahab of Israel'. This identification has been widely accepted, but it has recently been challenged. The arguments against the identification with the biblical Ahab are well presented and understandable, but is it reasonable that in the mid-9th century there was an 'Ahab' in Syria from a country whose name was very similar to 'Israel', yet he had no connection with the Ahab of the Bible? It is always possible, but common sense says it is not likely. [Footnote:] W. Gugler, Jehu und seine Revolution, Kampen 1996, 67-80. Gugler cites A.S. van der Woude, Zacharia (PredOT), Nijkerk 1984, 167, as the originator of the thesis, that the Achab from the monolith-inscription should be construed as a king from Northwestern Syria."

- ^ Reliefs from the Palace of Ashurnasirpal II: A Cultural Biography edited by Ada Cohen, Steven E. Kangas P:127

- ^ Kelle 2002.