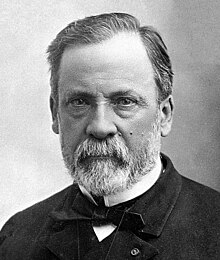

Louis Pasteur

Louis Pasteur (27 Desember 1822 – 28 September 1895) adalah ilmuwan kelahiran Perancis. Sebagai ilmuwan, ia berhasil menemukan cara mencegah pembusukan makanan hingga beberapa waktu lamanya dengan proses pemanasan yang biasa disebut pasteurisasi. Louis Pasteur memulai kariernya sebagai ahli fisika di sebuah sekolah lanjutan atas. Pada usia 26 tahun ia sudah menjadi profesor di Universitas Strasbourg, kemudian ia pindah ke Universitas Lille dan di sana pada tahun 1856 ia melakukan penemuan yang berarti sangat besar bagi bidang kedokteran. Penemuan awalnya adalah pasteurisasi yaitu mematikan bakteri yang ada di susu dengan pemanasan.

| Louis Pasteur | |

|---|---|

| |

| Lahir | 27 Desember 1822 Dole, Jura, Franche-Comté, Perancis |

| Meninggal | 28 September 1895 (umur 72) Stroke Marnes-la-Coquette, Hauts-de-Seine, Perancis |

| Tempat tinggal | Perancis |

| Kebangsaan | Perancis |

| Almamater | École Normale Supérieure |

| Karier ilmiah | |

| Bidang | Kimia Mikrobiologi |

| Institusi | Dijon Lycée Universitas Strasbourg Lille Universitas Sains dan Teknologi École Normale Supérieure |

| Mahasiswa ternama | Charles Friedel |

| Tanda tangan | |

| |

Louis Pasteur ilmuwan pendukung teori Biogenesis terkenal dengan teori "Omne ovum ex vivo omne vivum ex ovo"

Pasteur juga membuat obat untuk pencegah penyakit antraks dan suntikan melawan penyakit anjing gila rabies. Pada waktu itu orang yang digigit oleh anjing gila akan menderita penyakit yang disebut hidrofobia. Suntikan rabies Pasteur tidak hanya mencegah tetapi juga mengobati penyakit tersebut. Pada hari ulang tahunnya yang ke 70 para dokter dan ilmuwan dari seluruh dunia berkunjung ke Paris untuk menghormatinya. Sejak tahun 1888 karya Pasteur dilanjutkan di Institut Pasteur di Paris. Kini institut itu mempunyai cabang di 60 negara. Makamnya terdapat di bawah Institut tersebut, jenazahnya dimasukkan ke dalam peti mati terbuat dari marmer dan granit.

Pendidikan dan kehidupan awal

Louis Pasteur lahir pada 27 Desember 1822, di Dole, Jura, [[[Prancis]], di sebuah keluarga Katolik. [1] Dia adalah anak ketiga dari Jean-Joseph Pasteur dan Jeanne-Etiennette Roqui. Keluarga pindah ke Marnoz pada tahun 1826 dan kemudian ke Arbois pada tahun 1827. [2][3] Pasteur memasuki sekolah dasar pada tahun 1831. [4]

Dia adalah seorang siswa dengan nilai rata-rata di tahun-tahun awal, dan tidak terlalu akademis, karena minatnya hanya memancing dan membuat sketsa. [5] Dia menggambar banyak warna pastel dan potret orang tua, teman dan tetangganya. ref>Debré, Patrice (2000). Louis Pasteur. Diterjemahkan oleh Forster, Elborg. Baltimore: JHU Press. hlm. 12–13. ISBN 9780801865299.</ref> Pasteur mengikuti sekolah menengah di College d'Arbois. [6] Pada Oktober 1838, ia berangkat ke Paris untuk bergabung dengan Pensiun Barbet, tetapi menjadi rindu kampung halaman dan kembali pada bulan November. [7]

Pada tahun 1839, ia masuk ke Royal College di Besançon untuk belajar filsafat dan memperoleh gelar Bachelor of Letters pada tahun 1840. [8] Dia diangkat sebagai guru di perguruan tinggi Besançon sambil melanjutkan kursus ilmu derajat dengan matematika khusus. [9] Ia gagal ujian pertama pada 1841. Dia berhasil lulus baccalauréat scientifique (ilmu pengetahuan umum) gelar pada 1842 dari Dijon tetapi dengan tingkat biasa-biasa saja dalam kimia. [10]

Kemudian pada tahun 1842, Pasteur mengambil ujian masuk untuk École Normale Supérieure. [11] Dia lulus tes pertama, tetapi karena peringkatnya rendah, Pasteur memutuskan untuk tidak melanjutkan dan mencoba lagi tahun depan. [12] Dia kembali ke Pension Barbet untuk mempersiapkan tes. Dia juga menghadiri kelas di Lycée Saint-Louis dan kuliah Jean-Baptiste Dumas di Sorbonne. [13] Pada 1843, ia lulus ujian dengan peringkat tinggi dan memasuki École Normale Supérieure. [14] In 1845 he received the licencié ès sciences (Master of Science) degree.[15] Pada 1845 ia menerima gelar licencié ès science (Master of Science). [24] Pada tahun 1846, ia diangkat sebagai profesor fisika di Collège de Tournon (sekarang disebut Lycée Gabriel-Faure (fr)) di Ardèche, tetapi ahli kimia Antoine Jérôme Balard menginginkannya kembali di École Normale Supérieure sebagai asisten laboratorium lulusan (agrégé préparateur ). [25] Dia bergabung dengan Balard dan secara bersamaan memulai penelitiannya dalam kristalografi dan pada tahun 1847, dia menyerahkan dua tesisnya, satu dalam kimia dan yang lainnya dalam fisika. [16] He joined Balard and simultaneously started his research in crystallography and in 1847, he submitted his two theses, one in chemistry and the other in physics.[15][17]

Setelah melayani sebentar sebagai profesor fisika di Dijon Lycée pada tahun 1848, ia menjadi profesor kimia di Universitas Strasbourg, [18] di mana ia bertemu dan mendampingi Marie Laurent, puteri rektor universitas pada tahun 1849. Mereka menikah pada 29 Mei , 1849, [19] dan bersama-sama memiliki lima anak, hanya dua di antaranya selamat hingga dewasa, [20] tiga lainnya meninggal karena tifus.

Karir

Pasteur diangkat sebagai profesor kimia di Universitas Strasbourg pada 1848, dan menjadi ketua kimia pada 1852. [21] Pada 1854, ia diangkat sebagai dekan fakultas ilmu baru di Universitas Lille, di mana ia memulai studinya tentang fermentasi. [22] Pada kesempatan inilah Pasteur mengutarakan ucapannya yang sering dikutip: "dans les champs de l'observation, le hasard ne favorise que les esprits préparés" ("Dalam bidang pengamatan, kesempatan hanya mendukung pikiran yang dipersiapkan"). [23]

Pada 1857, ia pindah ke Paris sebagai direktur studi ilmiah di École Normale Supérieure di mana ia mengambil kontrol dari 1858 hingga 1867 dan memperkenalkan serangkaian reformasi untuk meningkatkan standar kerja ilmiah. Ujian menjadi lebih kaku, yang mengarah pada hasil yang lebih baik, persaingan yang lebih besar, dan peningkatan prestise. Namun banyak dari ketetapannya yang kaku dan otoriter, yang menyebabkan dua pemberontakan mahasiswa yang serius. Selama "pemberontakan kacang" ia memutuskan bahwa rebusan daging kambing, yang ditolak oleh para siswa, akan disajikan dan dimakan setiap Senin. Pada kesempatan lain ia mengancam akan mengusir siswa yang ketahuan merokok, dan 73 dari 80 siswa di sekolah mengundurkan diri. [24]

Pada 1863, ia diangkat sebagai profesor geologi, fisika, dan kimia di École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts, posisi yang dipegangnya hingga pengunduran dirinya pada 1867. Pada 1867, ia menjadi ketua kimia organik di Sorbonne, [25] tetapi ia kemudian menyerah karena kesehatan yang buruk. [26] Pada tahun 1867, laboratorium kimia fisiologi École Normale dibuat atas permintaan Pasteur, [27] dan dia adalah direktur laboratorium dari 1867 hingga 1888. [28] Di Paris, ia mendirikan Pasteur Institute pada tahun 1887, di mana ia menjadi direkturnya selama sisa hidupnya. [29][30]

Kehidupan pribadi

Iman dan spiritualitas

Cucu laki-lakinya, Louis Pasteur Vallery-Radot, menulis bahwa Pasteur telah menahan dari latar belakang Katoliknya hanya sebuah spiritualisme tanpa praktik keagamaan. [31] Namun, pengamat Katolik sering mengatakan bahwa Pasteur tetap menjadi orang Kristen yang beriman sepanjang hidupnya, dan menantunya menulis, dalam biografi dirinya:

Iman yang absolut pada Tuhan dan dalam Keabadian, dan keyakinan bahwa kekuatan untuk kebaikan yang diberikan kepada kita di dunia ini akan diteruskan di luarnya, adalah perasaan yang meliputi seluruh hidupnya; kebajikan Injil pernah ada padanya. Penuh rasa hormat untuk bentuk agama yang telah menjadi nenek moyangnya, ia datang hanya untuk itu dan alami untuk bantuan rohani dalam minggu-minggu terakhir hidupnya. [32]

Maurice Vallery-Radot, cucu lelaki dari menantu laki-laki dari Pasteur dan Katolik yang vokal, juga berpendapat bahwa Pasteur pada dasarnya tetap Katolik. [33] Menurut kedua Pasteur Vallery-Radot dan Maurice Vallery-Radot, kutipan terkenal berikut yang dikaitkan dengan Pasteur adalah apocryphal: [34] "Semakin saya tahu, semakin mendekati iman saya bahwa petani Breton. Bisakah saya tahu semua saya akan memiliki iman istri petani Breton ". [35] Menurut Maurice Vallery-Radot, [36] kutipan palsu muncul untuk pertama kalinya tak lama setelah kematian Pasteur. ref>In Pasteur's Semaine religieuse ... du diocèse de Versailles, October 6, 1895, p. 153.</ref> Namun, meskipun keyakinannya pada Tuhan, telah dikatakan bahwa pandangannya adalah pandangan bebas daripada seorang Katolik, yang lebih spiritual daripada seorang yang religius. [37][38]] Dia juga menentang pencampuran sains dengan agama. [39][40]

Kematian

Pada 1868, Pasteur menderita stroke yang melumpuhkan sisi kiri tubuhnya, tetapi ia sembuh. ref>Vallery-Radot, René (1919). The Life of Pasteur. Diterjemahkan oleh Devonshire, R. L. London: Constable & Company. hlm. 159–168.</ref> Stroke atau uremia pada tahun 1894 sangat mengganggu kesehatannya. [[41][42][43] Gagal untuk sepenuhnya pulih, ia meninggal pada 28 September 1895, dekat Paris. [44] Dia diberi pemakaman kenegaraan dan dimakamkan di Katedral Notre Dame, tetapi jenazahnya diinterklamasi di Institut Pasteur di Paris, [45] di dalam lemari besi yang tercakup dalam penggambaran prestasinya dalam mosaik Byzantium. [46]

Lihat pula

Referensi

- ^ name="catholic intro"

- ^ Debré, Patrice (2000). Louis Pasteur. Diterjemahkan oleh Forster, Elborg. Baltimore: JHU Press. hlm. 6–7. ISBN 9780801865299.

- ^ Robbins, Louise (2001). Louis Pasteur and the Hidden World of Microbes. New York: Oxford University Press. hlm. 14. ISBN 9780195122275.

- ^ Debré, Patrice (2000). Louis Pasteur. Diterjemahkan oleh Forster, Elborg. Baltimore: JHU Press. hlm. 8. ISBN 9780801865299.

- ^ name="catholic intro"

- ^ Robbins, Louise (2001). Louis Pasteur and the Hidden World of Microbes. New York: Oxford University Press. hlm. 15. ISBN 9780195122275.

- ^ Debré, Patrice (2000). Louis Pasteur. Diterjemahkan oleh Forster, Elborg. Baltimore: JHU Press. hlm. 11–12. ISBN 9780801865299.

- ^ Keim, Albert; Lumet, Louis (1914). Louis Pasteur. Frederick A. Stokes Company. hlm. 10, 12.

- ^ Debré, Patrice (2000). Louis Pasteur. Diterjemahkan oleh Forster, Elborg. Baltimore: JHU Press. hlm. 14, 17. ISBN 9780801865299.

- ^ Debré, Patrice (2000). Louis Pasteur. Diterjemahkan oleh Forster, Elborg. Baltimore: JHU Press. hlm. 19–20. ISBN 9780801865299.

- ^ Robbins, Louise (2001). Louis Pasteur and the Hidden World of Microbes. New York: Oxford University Press. hlm. 18. ISBN 9780195122275.

- ^ Debré, Patrice (2000). Louis Pasteur. Diterjemahkan oleh Forster, Elborg. Baltimore: JHU Press. hlm. 20–21. ISBN 9780801865299.

- ^ Keim, Albert; Lumet, Louis (1914). Louis Pasteur. Frederick A. Stokes Company. hlm. 15–17.

- ^ Debré, Patrice (2000). Louis Pasteur. Diterjemahkan oleh Forster, Elborg. Baltimore: JHU Press. hlm. 23–24. ISBN 9780801865299.

- ^ a b Debré, Patrice (2000). Louis Pasteur. Diterjemahkan oleh Forster, Elborg. Baltimore: JHU Press. hlm. 502. ISBN 9780801865299.

- ^ Debré, Patrice (2000). Louis Pasteur. Diterjemahkan oleh Forster, Elborg. Baltimore: JHU Press. hlm. 29–30. ISBN 9780801865299.

- ^ Keim, Albert; Lumet, Louis (1914). Louis Pasteur. Frederick A. Stokes Company. hlm. 28–29.

- ^ Keim, Albert; Lumet, Louis (1914). Louis Pasteur. Frederick A. Stokes Company. hlm. 37–38.

- ^ Holmes, Samuel J. (1924). Louis Pasteur. Harcourt, Brace and company. hlm. 34–36.

- ^ Robbins, Louise E. (2001). Louis Pasteur and the Hidden World of Microbes. Oxford University Press. hlm. 56. ISBN 978-0-190-28404-6.

- ^ Debré, Patrice (2000). Louis Pasteur. Diterjemahkan oleh Forster, Elborg. Baltimore: JHU Press. hlm. 502–503. ISBN 9780801865299.

- ^ name=Chirality

- ^ L. Pasteur, "Discours prononcé à Douai, le 7 décembre 1854, à l'occasion de l'installation solennelle de la Faculté des lettres de Douai et de la Faculté des sciences de Lille" (Speech delivered at Douai on December 7, 1854 on the occasion of his formal inauguration to the Faculty of Letters of Douai and the Faculty of Sciences of Lille), reprinted in: Pasteur Vallery-Radot, ed., Oeuvres de Pasteur (Paris, France: Masson and Co., 1939), vol. 7, page 131.

- ^ name=Debre>Debré, Patrice (2000). Louis Pasteur. Translated by Elborg Forster. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. hlm. 119–120. ISBN 9780801865299. Diakses tanggal 27 January 2015.

- ^ name="Debré & Patrice pp. 505-7">Debré, Patrice (2000). Louis Pasteur. Diterjemahkan oleh Forster, Elborg. Baltimore: JHU Press. hlm. 505–507. ISBN 9780801865299.

- ^ Vallery-Radot, René (1919). The Life of Pasteur. Diterjemahkan oleh Devonshire, R. L. London: Constable & Company. hlm. 246.

- ^ name="Debré & Patrice pp. 505-7"

- ^ Heilbron, J. L., ed. (2003). "Pasteur, Louis". The Oxford Companion to the History of Modern Science. Oxford University Press. hlm. 617. ISBN 978-0-199-74376-6.

- ^ name=fein

- ^ name=van

- ^ Pasteur Vallery-Radot, Letter to Paul Dupuy, 1939, quoted by Hilaire Cuny, Pasteur et le mystère de la vie, Paris, Seghers, 1963, p. 53–54. Patrice Pinet, Pasteur et la philosophie, Paris, 2005, p. 134–135, quotes analogous assertions of Pasteur Vallery-Radot, with references to Pasteur Vallery-Radot, Pasteur inconnu, p. 232, and André George, Pasteur, Paris, 1958, p. 187. According to Maurice Vallery-Radot (Pasteur, 1994, p. 378), the false quotation appeared for the first time in the Semaine religieuse ... du diocèse de Versailles, October 6, 1895, p. 153, shortly after the death of Pasteur.

- ^ (Vallery-Radot 1911, vol. 2, p. 240)

- ^ Vallery-Radot, Maurice (1994). Pasteur. Paris: Perrin. hlm. 377–407.

- ^ Pasteur Vallery-Radot, Letter to Paul Dupuy, 1939, quoted by Hilaire Cuny, Pasteur et le mystère de la vie, Paris, Seghers, 1963, p. 53–54.

- ^ name="catholic intro"

- ^ Pasteur, 1994, p. 378.

- ^ Joseph McCabe (1945). A Biographical Dictionary of Ancient, Medieval, and Modern Freethinkers. Haldeman-Julius Publications. Diakses tanggal 11 August 2012.

The anonymous Catholic author quotes as his authority the standard biography by Vallery-Radot, yet this describes Pasteur as a freethinker; and this is confirmed in the preface to the English translation by Sir W. Osler, who knew Pasteur personally. Vallery-Radot was himself a Catholic yet admits that Pasteur believed only in "an Infinite" and "hoped" for a future life. Pasteur publicly stated this himself in his Academy speech in 1822 (in V.R.). He said: "The idea of God is a form of the idea of the Infinite whether it is called Brahma, Allah, Jehova, or Jesus." The biographer says that in his last days he turned to the Church but the only "evidence" he gives is that he liked to read the life of St. Vincent de Paul, and he admits that he did not receive the sacraments at death. Relatives put rosary beads in his hands, and the Catholic Encyclopedia claims him as a Catholic in virtue of the fact and of an anonymous and inconclusive statement about him. Wheeler says in his Dictionary of Freethinkers that in his prime Pasteur was Vice-President of the British Secular (Atheist) Union; and Wheeler was the chief Secularist writer of the time. The evidence is overwhelming. Yet the Catholic scientist Sir Bertram Windle assures his readers that "no person who knows anything about him can doubt the sincerity of his attachment to the Catholic Church," and all Catholic writers use much the same scandalous language.

- ^ Patrice Debré (2000). Louis Pasteur. JHU Press. hlm. 176. ISBN 978-0-8018-6529-9.

Does this mean that Pasteur was bound to a religious ideal? His attitude was that of a believer, not of a sectarian. One of his most brilliant disciples, Elie Metchnikoff, was to attest that he spoke of religion only in general terms. In fact, Pasteur evaded the question by claiming quite simply that religion has no more place in science than science has in religion. ... A biologist more than a chemist, a spiritual more than a religious man, Pasteur was held back only by the lack of more powerful technical means and therefore had to limit himself to identifying germs and explaining their generation.

- ^ Joseph McCabe (1945). A Biographical Dictionary of Ancient, Medieval, and Modern Freethinkers. Haldeman-Julius Publications. Diakses tanggal 11 August 2012.

The anonymous Catholic author quotes as his authority the standard biography by Vallery-Radot, yet this describes Pasteur as a freethinker; and this is confirmed in the preface to the English translation by Sir W. Osler, who knew Pasteur personally. Vallery-Radot was himself a Catholic yet admits that Pasteur believed only in "an Infinite" and "hoped" for a future life. Pasteur publicly stated this himself in his Academy speech in 1822 (in V.R.). He said: "The idea of God is a form of the idea of the Infinite whether it is called Brahma, Allah, Jehova, or Jesus." The biographer says that in his last days he turned to the Church but the only "evidence" he gives is that he liked to read the life of St. Vincent de Paul, and he admits that he did not receive the sacraments at death. Relatives put rosary beads in his hands, and the Catholic Encyclopedia claims him as a Catholic in virtue of the fact and of an anonymous and inconclusive statement about him. Wheeler says in his Dictionary of Freethinkers that in his prime Pasteur was Vice-President of the British Secular (Atheist) Union; and Wheeler was the chief Secularist writer of the time. The evidence is overwhelming. Yet the Catholic scientist Sir Bertram Windle assures his readers that "no person who knows anything about him can doubt the sincerity of his attachment to the Catholic Church," and all Catholic writers use much the same scandalous language.

- ^ Patrice Debré (2000). Louis Pasteur. JHU Press. hlm. 176. ISBN 978-0-8018-6529-9.

Does this mean that Pasteur was bound to a religious ideal? His attitude was that of a believer, not of a sectarian. One of his most brilliant disciples, Elie Metchnikoff, was to attest that he spoke of religion only in general terms. In fact, Pasteur evaded the question by claiming quite simply that religion has no more place in science than science has in religion. ... A biologist more than a chemist, a spiritual more than a religious man, Pasteur was held back only by the lack of more powerful technical means and therefore had to limit himself to identifying germs and explaining their generation.

- ^ Debré, Patrice (2000). Louis Pasteur. Diterjemahkan oleh Forster, Elborg. Baltimore: JHU Press. hlm. 512. ISBN 9780801865299.

- ^ Keim, Albert; Lumet, Louis (1914). Louis Pasteur. Frederick A. Stokes Company. hlm. 206.

- ^ Vallery-Radot, René (1919). The Life of Pasteur. Diterjemahkan oleh Devonshire, R. L. London: Constable & Company. hlm. 458.

- ^ name="cohn"

- ^ Frankland, Percy; Frankland, Percy (1901). Pasteur. Cassell and Company. hlm. 217–219.

- ^ Campbell, D M (January 1915). "The Pasteur Institute of Paris". American Journal of Veterinary Medicine. Chicago, Ill.: D. M. Campbell. 10 (1): 29–31. Diakses tanggal February 8, 2010.

Bacaan lebih lanjut

- Debré, P. (1998). Louis Pasteur. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-5808-9.

- Duclaux, E.Translated by Erwin F. Smith and Florence Hedges (1920). Louis Pasteur: The History of a Mind. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: W. B. Saunders Company.

- Geison, Gerald L. (1995). The Private Science of Louis Pasteur. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-03442-7.

- Latour, Bruno (1988). The Pasteurization of France. Boston: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-65761-6.

- Reynolds, Moira Davison. How Pasteur Changed History: The Story of Louis Pasteur and the Pasteur Institute (1994)

- Williams, Roger L. (1957). Gaslight and Shadow: The World of Napoleon III, 1851-1870. NY: Macmillan Company. ISBN 0-8371-9821-6.

Pranala luar

- The Institut Pasteur – Yayasan yang didedikasikan untuk pencegahan dan pengobatan penyakit melalui penelitian biologi, pendidikan dan kegiatan kesehatan masyarakat

- The Pasteur Foundation – Sebuah organisasi nirlaba AS yang didedikasikan untuk mempromosikan misi Institut Pasteur di Paris. Arsip lengkap laporan berkala tersedia secara online sebagai bentuk penghormatan untuk Louis Pasteur.

- Pasteur's Papers on the Germ Theory

- The Life and Work of Louis Pasteur, Pasteur Brewing

- The Pasteur Galaxy

- Louis Pasteur featured on the 5 French Franc banknote from 1966.

- Germ Theory and Its Applications to Medicine and Surgery, 1878

- Louis Pasteur (1822-1895) profil, AccessExcellence.org

Karya lengkap milik Pasteur, BNF (Bibliothèque nationale de France)

- Pasteur Œuvre tome 1 – Dissymétrie moléculairePDF (Prancis)

- Pasteur Œuvre tome 2 – Fermentations et générations dites spontanéesPDF (Prancis)

- Comptes rendus de l’Académie des sciences Artikel diterbitkan oleh Pasteur (Prancis)